Dante Alighieri

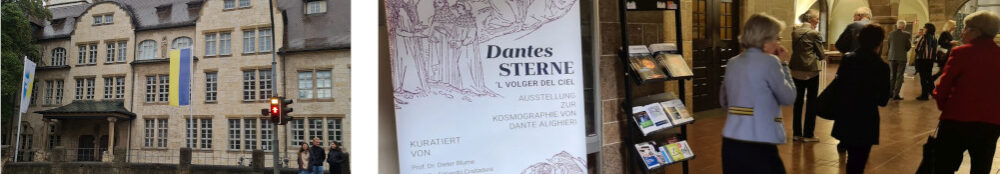

Derzeit (28. bis 30.10.) findet die Jahrestagung der Deutschen Dante-Gesellschaft in Jena statt. Ja, ich meine den Dichter Dante Alighieri und nicht die Deutsche Anwendervereinigung TEX e.V. Es gehört zum Allgemeinwissen, dass der Dichter um 1300 in seinem Gedicht Divina Comedia (Göttliche Komödie) nicht nur die damalige Gesellschaft karikiert und parodiert, sondern dass er dabei auch zahlreiche astronomische Bezüge hat. Er schrieb auf Italienisch und daher ist es – wie häufig ist es in der Literatur – so, dass diejenigen, die die Sprache exzellent beherrschen und Übersetzungen + Interpretationen schreiben, die Astronomie in diesem Texte überblättern. Manchmal werden astronomische Sentenzen missverstanden, weil man sie mit moderner Naivität oder eben Unkenntnis liest. Darum nutzte der Vorstand der Dante-Gesellschaft das Wahrzeichen des Tagungsortes, das Planetarium, um einerseits der Tagung eine außergewöhnliche Eröffnung zu bescheren und andererseits eine Naturwissenschaftshistorikerin “Dantes Sterne” erklären zu lassen. Die eigentliche Tagung findet dann an der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena statt.

Die Dante-Gesellschaft ist quasi ein Fan-Club für den Dichter und seine Zeit, ein Zusammenschluss (juristisch: gemeinnütziger Verein) von Menschen unterschiedlichster Bildungshintergründe, die sich gern mit diesen Themen beschäftigen. Wissenschaftliche Arbeiten auf diesem Gebiet kommen freilich vordergründig von RomanistInnen und KunsthistorikerInnen – aber wie auch in der Astronomie zahlreiche Hobby-AstronomInnen auf unterschiedlichste Art zur Forschung beitragen können (z.B. Citizen Science-Projekte zur Datenanalyse am Computer, Beobachtungen mit eigenem Teleskop, etc.), so können auch in der Dante-Gesellschaft alle mitmachen. Die Gesellschaft hat ihren Sitz formal in Weimar, arbeitet aber überregional. Sie können also herzlich gerne Mitglied werden!

Currently (28. to 30.10.) the annual conference of the German Dante Society is taking place in Jena. Yes, I mean the poet Dante Alighieri and not the German User Association TEX e.V. (abbrev.: DANTE). It is common knowledge that the poet around 1300 not only caricatures and parodies the society of that time in his poem Divina Comedia (Divine Comedy), but that he also has numerous astronomical references. He wrote in Italian and therefore, as is often the case in literature, those who have an excellent command of the language and write translations + interpretations skim over the astronomy in this text. Sometimes astronomical sentences are misunderstood, because one reads them with modern naivety or just ignorance. That is why the board of the Dante Society used the landmark of the conference venue, the planetarium, to give the conference an extraordinary opening on the one hand and to have a historian of natural sciences explain “Dante’s stars” on the other hand. The actual conference will then take place at the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena.

The Dante Society is quasi a fan club for the poet and his time, an association (legally: non-profit association) of people from different educational backgrounds who like to deal with these topics. Scientific work in this field comes primarily from Romance scholars and art historians – but just as in astronomy numerous amateur astronomers can contribute to research in various ways (e.g. Citizen Science projects for data analysis on the computer, observations with their own telescope, etc.), so too in the Dante Society everyone can participate. The society is formally based in Weimar, but works nationwide. So you are welcome to become a member!

Herr Blume sprach z.B. in seinem Vortrag über verschiedene Formen von Allegorien: sei es durch die Skulpturen auf Brunnen in der Stadt Florenz, Inschriften an Häusern, die sich die Volksregierung schuf oder Darstellungen der vier Kardinaltugenden, die man in Profanbauten wie auch in Kirchen jener Epoche der Selbstverwaltung durch Vertreter des Volkes fand. Frau Doering verglich die Dichtung Dantes mit Dichtungen seiner Zeitgenossen und stellte Gemeinsamkeiten und Unterschiede zu zeitgenössischen Florentinern heraus.

Mr. Blume, for example, spoke in his lecture about various forms of allegory: whether through the sculptures on fountains in the city of Florence, inscriptions on houses created by the popular government, or representations of the four cardinal virtues found in secular buildings as well as in churches of that era of self-government by representatives of the people. Ms. Doering compared Dante’s poetry with poetry by his contemporaries and highlighted similarities and differences with contemporary Florentines.

‘l volger del ciel – Zeiss-Planetarium Jena

Obwohl die Tagung offiziell zum Thema “Dante und die Stadt” ausgerichtet war und die Vorträge daher den historischen, kulturellen und wirtschaftlichen Hintergrund der Zeit Dantes beleuchteten, war durch die Eröffnung der Tagung im Planetarium Jena das Thema “Dante und die Sterne” während der ganzen Tagung ebenso prominent vertreten. Gefördert durch die Ernst-Abbe-Stiftung fand die Auftaktveranstaltung am Vorabend der Tagung im Planetarium Jena statt.

Wir zeigten den Sternhimmel, die Bewegung der Sterne im Lauf der Nacht und das wechselnde Erscheinungsbild des Sternhimmels mit den Jahreszeiten. Wir zeigten die Sternbilder des Tierkreises und wie sie damals zur Bestimmung von Jahr und Tag genutzt wurde – denn das kann man schon bei Aratos nachlesen und in seiner Rezeption durch Antike, Spätantike und Mittelalter verfolgen. Da es bei Dante einen starken Fokus auf das Sternbild der Zwillinge gibt, wiederholte sich dieses Thema in der Kuppel und wir zeigten die Version dieses Sternbilds von Michael Scotus und die zu Dantes Zeit populär war, das Füllhorn, das er im Kleinen Wagen sah sowie die Sternbilder der Leidener Aratea, die ich hier bereits vor zwei Jahren installiert hatte. Die dialogische (oder mit Blick auf die Rezitationen sogar trialogische) Form unseres Vortrags kam insgesamt sehr gut an: Mehrere Gäste sagten hinterher erfreut, sie hätten dem gern noch länger zugehört. 🙂

‘l volger del ciel – Zeiss-Planetarium Jena

Although the official theme of the conference was “Dante and the City” and the lectures therefore highlighted the historical, cultural and economic background of Dante’s time, the opening of the conference in the Jena Planetarium meant that the theme of “Dante and the Stars” was equally prominent throughout the conference. Sponsored by the Ernst Abbe Foundation, the opening event took place on the eve of the conference at the Jena Planetarium.

We showed the starry sky, the movement of the stars in the course of the night and the changing appearance of the starry sky with the seasons. We showed the constellations of the zodiac and how it was used at that time to determine the year and the day – because you can already read about this in Aratos and follow it in its reception through antiquity, late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Since there is a strong focus on the constellation of the Twins in Dante, this theme was repeated in the dome and we showed the version of this constellation by Michael Scotus and which was popular in Dante’s time, the cornucopia he saw in the Little Dipper, and the constellations of the Leiden Aratea, which I had already installed here two years ago. The dialogic (or with regard to the recitations even trialogic) form of our lecture was on the whole very well received: Several guests said afterwards with pleasure that they would have liked to listen to it even longer. 🙂

Seit vielen Monaten hatten der Vorstand der Deutschen Dante-Gesellschaft (Herr PD Dr. Ellerbrock, Herr Dr. Zöll), die Herren Prof. Dr. Costadura und Herr Prof. Dr. Blume und das Team des Planetariums für diesen Abend gearbeitet, um die 90minütige Performance zu ermöglichen: Rezitationen des Italienischen wurden mit Kommentaren aus Kunstgeschichte und Astronomie(geschichte) begleitet. Barbara Schöneberger sagte mal in einem Interview, dass bei einer Moderatorin das wichtigste sei, welches Kleid sie trage. Ich wähle meine Kleider stets planetariums-dunkel und für den Veranstalter bzw. zum Thema passend (das berühmte Porträt von Herrn Alighieri zeigt ihn in roter Robe) und es ist fast das unwichtigste in der Vorbereitung: die mehr oder weniger zahlreichen Stunden an den Computern im HomeOffice und in der Kuppel, die ich verbringe, um historische Sternbilder zu erforschen, zu zeichnen und an die richtige Stelle am Sternhimmel zu basteln ist wahrlich überwiegend.

For many months the board of the German Dante Society (PD Dr. Ellerbrock, Dr. Zöll), Prof. Dr. Costadura and Prof. Dr. Blume and the team of the Planetarium had worked for this evening to make the 90 minute performance possible: Recitations of Italian were accompanied by commentary from art history and astronomy (history). Barbara Schöneberger once said in an interview that the most important thing for a presenter is which dress she wears. I always choose my dresses planetarium-dark and suitable for the presenter or the topic (the famous portrait of Mr. Alighieri shows him in red robe) and it is almost the least important thing in the preparation: the more or less numerous hours at the computers in the home office and in the dome that I spend researching historical constellations, drawing them and tinkering them into the right place in the starry sky is truly predominantly

Wie Dante zu Ostern 1300 eine Jenseitsreise unternimmt, mit seinem imaginären Freund Vergil (dem römischen Dichter, der ein anständiger Mann und Dantes Vorbild war – der jedoch nie das Antlitz des christlichen Gottes sehen darf, weil er nunmal v.Chr. gestorben ist und daher leider kein Christ war) die Vorhölle passiert, durch das Höllentor in die Hölle eintritt, sich anschaut, welche Qualen die dort bestraften Seelen durchleiden müssen (z.B. auf ewig als Liebespaar verbunden zu sein), schließlich Läuterung erfährt und dabei hin und wieder mit den Seelen Dialoge führt, so lässt auch die Dante-Gesellschaft in ihrer Tagung verschiedenste Aspekte des Lebens in der Stadt im Allgemeinen und in Florenz im besonderen Revue passieren.

Just as Dante undertakes an afterlife journey at Easter 1300, passes through limbo with his imaginary friend Virgil (the Roman poet who was a decent man and Dante’s role model – but who was never allowed to see the face of the Christian God because he died before Christ and was therefore unfortunately not a Christian), enters hell through the gates of hell, sees what torments the souls punished there have to endure (e.g. being joined together as lovers for eternity) and finally experiences purification. In the same way that the Dante Society, in its conference, reviews various aspects of life in the city in general and in Florence in particular, the Dante Society also looks at the torments that the souls punished there have to endure (e.g., being bound together forever as lovers), finally undergoing purification and, in the process, having dialogues with the souls now and then.

“Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate!” in Jena

Dieser berühmte Satz steht laut Dante auf dem Höllentor, das Dante passiert, um dann der christlichen Gesellschaft durch subtilen Witz und Scharfsinn ihre Alogik und Ungerechtigkeiten vorzuführen. Es gehört zum Florentiner Selbstverständnis in dieser Zeit, dass man Dinge mit Humor nimmt und dass die Künstler vor den Wissenschaftlern die wahren Erkenntnisträger sind. Das Stück hat etwas satirisches, heißt aber Komödie und parodiert sich damit auch ein Stück weit selbst (warum es so heißt, darüber streiten sich schlauere Gelehrte: das kommentiere ich hier nicht). Ich kann Ihnen versichern, die Veranstalter sind jetzt guter Dinge und immer noch voller Vorfreude und Hoffnung auf die Früchte ihrer Arbeit, so dass die Tagung bisher jedenfalls eine Bereicherung war. Auch wenn sie vllt. bisweilen zwischenzeitlich ihre Hoffnung fahren gelassen haben, sind sie nun auf dem besten Wege, diese zurückzuerlangen.

Die Tagung wird morgen mit einer Rezitation aus dem Paradies schließen und dann werden die Tagungsteilnehmenden vom Bahnhof “Jena Paradies” in alle Winde abreisen. Vorher gibt es aber noch ein wenig Kunst zu erleben.

Nach der Eröffnung der Tagung fanden/ finden der Abendempfang und die Vorträge im Hauptgebäude der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena statt. Das Paradies rühmt sich Jena zu haben (den Park am Bahnhof), so dass man den Tagungsort vllt. eher am Ende der Jenseitsreise verorten möchte. Wo in Jena das Höllentor ist, wissen aber nur Eingeweihte. 😉

“Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate!” in Jena

This famous phrase, according to Dante, is written on the gate of hell, which Dante passes, then demonstrates to Christian society its alogic and injustices through subtle wit and acumen. It is part of the Florentine self-image at this time to take things with humor and that the artists are the true knowledge bearers before the scientists. The play has something satirical about it, but it is called a comedy and thus parodies itself to some extent (why it is called that is a matter of dispute among cleverer scholars: I won’t comment on that here). I can assure you, the organizers are now in good spirits and still full of anticipation and hope for the fruits of their labor, so the conference has been an enrichment so far in any case. Even if they may have temporarily lost hope, they are now well on the way to regaining it.

The conference will close tomorrow with a recitation from Paradise and then the conference participants will depart from the station “Jena Paradies” to all winds. But before that there is still some art to experience.

After the opening of the conference the evening reception and the lectures took place in the main building of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena. Paradise boasts Jena to have (the park at the station), so that one would like to locate the conference venue vllt rather at the end of the beyond journey. Where in Jena the gate of hell is, however, only insiders know 😉

Die Erde bei Dante

Die Erde bei Dante ist eine Kugel. Wie immer im Mittelalter und in der Antike.

Es ist eine populäre Fehlvorstellung, dass das Wissen um diese Kugelgestalt irgendwann verloren gegangen sei. Dieses Wissen hat es immer und bei allen gegeben (außer vllt bei Verschwörungstheoretikern, die es ja heute auch noch gibt). Die Größe der Erde war seit Eratosthenes (3. Jh. v.Chr.) bekannt und dass die Erde eine Kugel ist, wusste man seit ca. dem 6. Jh. v.Chr. Aristoteles schreibt es explizit mit zahlreichen Argumenten und jeder Aristoteles-Kopist im Mittelalter musste das wissen und überzeugt sein. Auch die christlichen Könige und religiösen Würdenträger im Mittelalter haben stets die Kugelgestalt der Erde in ihrer Herrschaftssymbolik benutzt. Das bekannteste Beispiel ist vermutlich der Reichsapfel, der Herrschaft über die Erde beansprucht. Das einzige, was man damals noch nicht so gut kannte, war die Verteilung der Landmassen auf dem Globus: Amerika und Australien waren unbekannt, die genaue Verteilung der Inseln zwischen China, Japan und Australien (Indonesien, Papua Neuguinea, und mehr von Ozeanien) war nicht bekannt und der eurasische Kontinent wurde in seinen Abmessungen zu groß eingeschätzt. Daher stimmen die Sonnenstände nicht haargenau, die Dante in seiner Comedia für Spanien, Indien und Jerusalem angibt – aber dass er das Prinzip der Zeitzonen auf dem Kugelglobus verstanden hatte, daran gibt es keinen Zweifel.

Wir haben auf unserem gebastelten Modell-Globus a) Jerusalem, b) Spanien, c) die Ganges-Mündungen markiert, die bei Dante wiederholt vorkommen. Wir haben auch den Ort für seinen Läuterungsberg, d.h. die Antipode für Jerusalem markiert und witzigerweise befindet sich dort auf dem Behaim-Globus eine Insel. Ob das Zufall ist?

Häufig hört man die falsche Unterstellung, dass die Erde als Scheibe gedacht worden sei. Das ist falsch und weil es für die richtige Interpretation des Textes wichtig ist, haben wir zwei Erdgloben in eine kleine Ausstellung gestellt, die für die Dauer der Ausstellung zu betrachten ist: ein Globus aus der Sammlung der Physikdidaktik der Universität und eine Reproduktion des Behaim-Globus (Nürnberg 1492), also noch ohne Amerika: selbst tapeziert.

Dante’s Earth

The earth in Dante is a sphere. As always in the Middle Ages and in antiquity.

It is a popular misconception that the knowledge about this spherical shape has been lost sometime. This knowledge has always existed and with all (except perhaps with conspiracy theorists, who still exist today). The size of the earth was known since Eratosthenes (3rd century B.C.) and that the earth is a sphere, one knew since approx. the 6th century B.C. Aristotle writes it explicitly with numerous arguments and every Aristotle copyist in the Middle Ages had to know this and be convinced. Also the Christian kings and religious dignitaries in the Middle Ages always used the spherical shape of the earth in their symbols of rule. The most famous example is probably the orb, which claims dominion over the earth. The only thing that was not well known at that time was the distribution of the land masses on the globe: America and Australia were unknown, the exact distribution of the islands between China, Japan and Australia (Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and more of Oceania) was not known, and the Eurasian continent was estimated too large in its dimensions. Therefore, the positions of the sun, which Dante gives in his Comedia for Spain, India and Jerusalem, are not exactly correct – but that he had understood the principle of the time zones on the spherical globe, there is no doubt.

We have marked on our made model globe a) Jerusalem, b) Spain, c) the mouths of the Ganges, which occur repeatedly in Dante. We have also marked the place for his mountain of purification, i.e. the antipode for Jerusalem and funnily enough there is an island on the Behaim globe. Whether this is a coincidence?

Often one hears the false insinuation that the earth was thought to be a disk. This is wrong and because it is important for the correct interpretation of the text, we have placed two terrestrial globes in a small exhibition, which can be viewed for the duration of the exhibition: a globe from the collection of the Physics Didactics of the University and a reproduction of the Behaim globe (Nuremberg 1492), so still without America: wallpapered itself

Klar erkennbar ist übrigens auf dem Behaim-Globus auch der Tierkreis: Man hat diese Linie stets auf Erdgloben eingezeichnet, obwohl sie eigentlich an den Himmel gehört.

By the way, the zodiac is also clearly visible on the Behaim globe: This line has always been drawn on earth globes, although it actually belongs to the sky.

Lectura Dantis – Paradiso XVII

In der Lectura Dantis wurde das Thema der Stadt bei Dante nochmals thematisiert. Es kommen nur wenige Städte namentlich vor, im Wesentlichen sind das Florenz, das theologische Jerusalem als Zentrum der Christenheit und Wohnsitz ihres Gottes und Babylon als Gleichsetzung mit der Hölle, die allerdings geographisch woanders liegt als das theologische Babel. Der Referent der Lectura Dantis, PD Dr. Philip Stockbrugger, reflektiert den Verlauf der Handlung in der Comedia, während dessen Dante durch die verschiedenen Jenseitsreiche wandert und durch das Gesehene sowie Gespräche mit seinen Begegnungen immer tiefere Einsichten erlangt. Bereits am Anfang der Comedia stellt sich Dante einem (christlichen) Propheten oder später mit einem (griechisch-antiken) Halbgott gleich, indem er z.B. seinen Lebenslauf mit dem Schicksal des ungerecht verstoßenen Hippolytos parallelisiert. Nach Durchlaufen verschiedener edukativer Dialoge und Erkenntnisstufen, so folgert der Referent, sei Dante nun wirklich “ausgestattet mit dem Wissen eines Propheten. Aber was kann er damit anfangen?”

Ich glaube, hier sehen wir wiedereinmal die Aktualität der Göttlichen Komödie und ihre Relevanz für die heutige Zeit, denn diese Frage haben sich wohl fast alle Habilitierten schon gestellt (auch Menschen mit zwei Dr-Graden statt Habiitation übrigens).

Lectura Dantis – Paradiso XVII

In the Lectura Dantis, the theme of the city was once again addressed in Dante. Only a few cities are mentioned by name, essentially Florence, the theological Jerusalem as the center of Christianity and the residence of its God, and Babylon as an equation with Hell, which, however, is geographically located somewhere else than the theological Babel. The speaker of the Lectura Dantis, PD Dr. Philip Stockbrugger, reflects on the course of the plot in the Comedia, during which Dante wanders through the various realms of the afterlife, gaining ever deeper insights through what he sees as well as conversations with his encounters. Already at the beginning of the Comedia, Dante equates himself with a (Christian) prophet or, later, with a (Greek-ancient) demigod, for example, by paralleling his course of life with the fate of the unjustly cast out Hippolytus. After passing through various eductive dialogues and stages of cognition, the speaker concludes, Dante is now truly “endowed with the knowledge of a prophet. But what can he do with it?”

I think, here we see once again the topicality of the Divine Comedy and its relevance for today, because this question has probably been asked by almost all habilitated people (even people with two Dr degrees instead of habiitation, by the way).

Abschluss der Tagung

Den Abschluss der Tagung bildete ein Konzert von neun Studierenden der Alten Musik aus Weimar. Sie haben einige Werke interpretiert, die aus der Zeit von Dante überliefert sind. Genau genommen, so berichtet der Dozent der Hochschule Martin Erhardt, sind aus der Zeit von Dante (um 1300) keine Schriften erhalten. Allerdings gibt es den Codex Squarcialupi, der etwa ein Jahrhundert später datiert. Die Musikgeschichte weiß, dass Musik als lebendiges Medium damals nicht aufgeschrieben wurde, solange sie praktiziert wurde. In einer Zeit, in der Musik nur dadurch existierte, dass sie live aufgeführt wurde und in der es keine Aufzeichnungsmöglichkeiten und Speichermöglichkeit für Klänge gab, war Musik nur im Genuss des Moments erfahrbar. Solange Musik live weitergegeben wurde, brauchte man sie nicht zu notieren und machte man sich diese Mühe nicht, weil jede Art der Notation ja nur Bruchteile der Gesamtwerkes darstellt: Musik ist (nach Nelson Goodman) eine allographische Kunst und keine autographische (wie Malerei), d.h. ein Notenblatt allein ist noch keine Musik und selbst wenn zwei Interpretationen der Noten sich strikt an diese halten würden, könnten sie grundverschieden klingen (z.B. wenn man verschiedene Instrumente oder Stimmen benutzt). Man notierte damals Musik also erst dann, wenn man befürchtete, nicht mehr live weitergeben zu können, was ursprünglich damit gemeint war. Die Notation einer Musik bedeutete quasi, dass sie dabei war, auszusterben.

Da jede Notation Lücken hat, waren die Studierenden der Alten Musik genauso im Bereich von Rekonstruktion (Kreativität) und historischer Korrektheit durch genaues Studium von Quellen, Epoche und Kontext unterwegs wie ich das mit meinen historischen Sternbildern bin. Ich fand es bereichernd, neben meiner eigenen “Kunst”form in Form von Visualisierungen am Sternhimmel hier auch einmal die Sonifikation des Zeitgeistes zu erleben.

Conclusion of the conference

The conclusion of the conference was a concert by nine students of early music from Weimar. They interpreted some works that have been handed down from the time of Dante. Strictly speaking, as reported by Martin Erhardt, a lecturer at the college, no writings have survived from Dante’s time (around 1300). However, there is the Codex Squarcialupi, which dates about a century later. Music history knows that music as a living medium was not written down at that time, as long as it was practiced. At a time when music existed only by being performed live, and when there were no means of recording or storing sounds, music could be experienced only in the enjoyment of the moment. As long as music was performed live, there was no need to notate it and no effort was made to do so, because any kind of notation represents only fractions of the whole work: Music is (according to Nelson Goodman) an allographic art and not an autographic one (like painting), i.e. a sheet of music alone is not music and even if two interpretations of the notes would strictly adhere to it, they could sound fundamentally different (e.g. if different instruments or voices were used). So at that time, music was notated only when one feared that one would no longer be able to pass on live what was originally meant by it. The notation of a music meant, so to speak, that it was about to die out.

Since all notation has gaps, early music students were as much in the realm of reconstruction (creativity) and historical accuracy through close study of sources, period and context as I am with my historical constellations. I found it enriching to experience the sonification of the zeitgeist here for once, in addition to my own “art” form in the form of visualizations in the starry sky.

PS: Was mich an dieser Tagung am allermeisten beeindruckte:

Es war eine Tagung von Geisteswissenschaftlern, aber alle hielten sich perfekt an die Zeitvorgabe! Niemand überzog die Redezeit und die Pausen waren stets von der angekündigten Länge! Es geht also. Ich verstehe nicht, warum andere Wissenschaftler immer der Meinung sind, dass man sich an Zeit- und Terminvorgaben nicht halten müsse?! (!!)

Eine schöne Erinnerung und auch Aufforderung sich mit diesem Meisterwerk der italienischen Literatur zu beschäftigen.

Das ist so großartig . Ein Treffpunkt für Dichter in Deutschland. eine wundervolle Veranstaltung. wo die Kunst spricht.