Meghalayan oder Anthropozän? In welcher erdgeschichtlichen Zeit leben wir denn nun?

Grönlandium, Northgrippium, Meghalayum – was ist das denn?

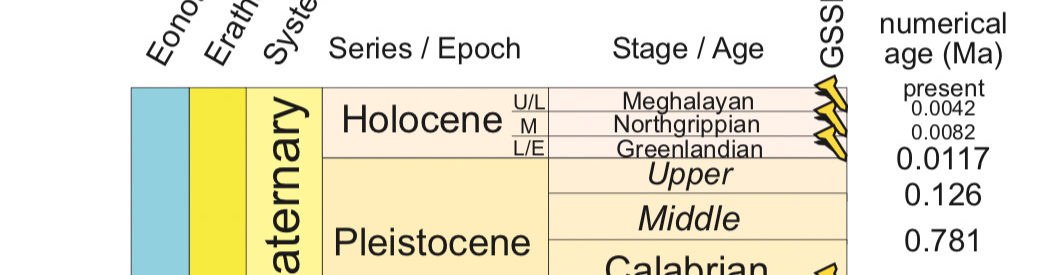

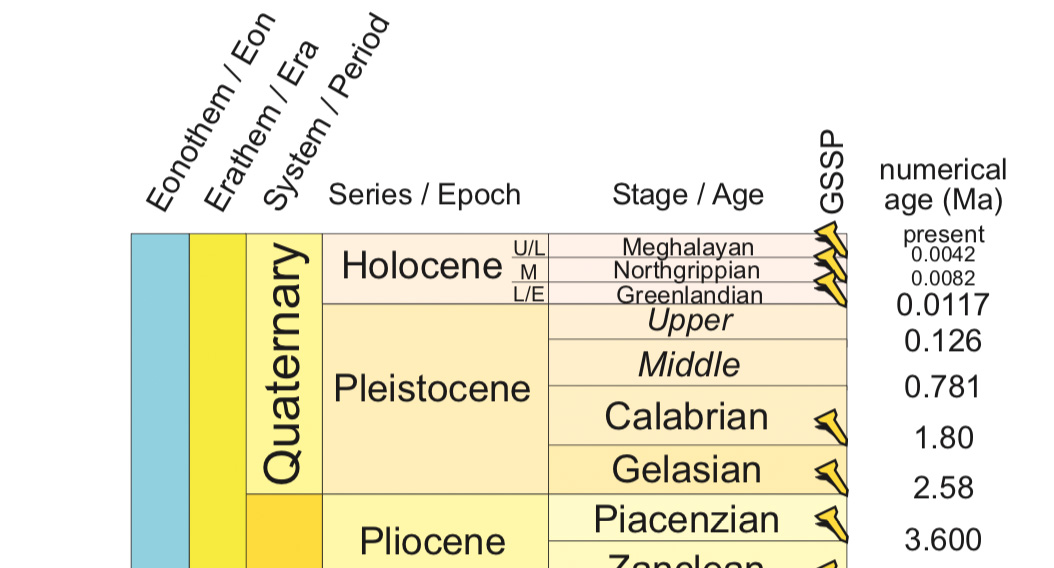

Derzeit erscheinen mehr oder weniger aufgeregte Beiträge in den (sozialen) Medien zur gerade veröffentlichten, formalisierten neuen Untergliederung des Holozäns, also der erdgeschichtlichen Epoche nach der letzten Eiszeit. Bisher existierten die Begriffe unteres, mittleres und oberes Holozän, aber diese wurden informell und daher eben auch recht unterschiedlich gebraucht, nun gibt es also als Konkretisierung ein Greenlandian, Northgrippian und Meghalayan („eingedeutscht“ wären dies Grönlandium, Northgrippium und Meghalayum). (Formal liegen diese auf der Skala von “Stufen” (wenn die Sedimente betrachtet werden) bzw. “Alter”, wenn die Zeit betrachtet wird, definieren aber gleichzeitig die “Subserien/Subepochen” des Holozäns, doch das dürfte nur Spezialisten interessieren). Das Greenlandian und damit das Holozän begann wie gehabt 11.700 Jahre vor “heute”, das Northgrippian 8200 Jahre vor “heute” und das Meghalayan 4200 Jahre vor “heute” (zu “heute” siehe weiter unten).

Ist damit das Anthropozän “gestorben”?

Soweit so gut, aber heißt dies nun, dass damit das Anthropozän „abgeschafft“ oder „abgelehnt“ wäre? Dies scheinen manche zu vermuten. Andere witzeln, diese geologische Zeittabelle würde die Namen häufiger wechseln, als die Kneipen in St. Pauli. Vor allem britische und US-amerikanische Medien berichteten bislang, teils auch zu angeblichen Kontroversen, auch der ORF brachte bereits eine Meldung und ja, selbst aus der zuständigen Dachorganisation IUGS kamen einige missverständliche Äußerungen. In Deutschland häufen sich bei mir als Mitglied der Working Group on the “Anthropocene” (AWG) die Anfragen. Daher hier eine Klärung.

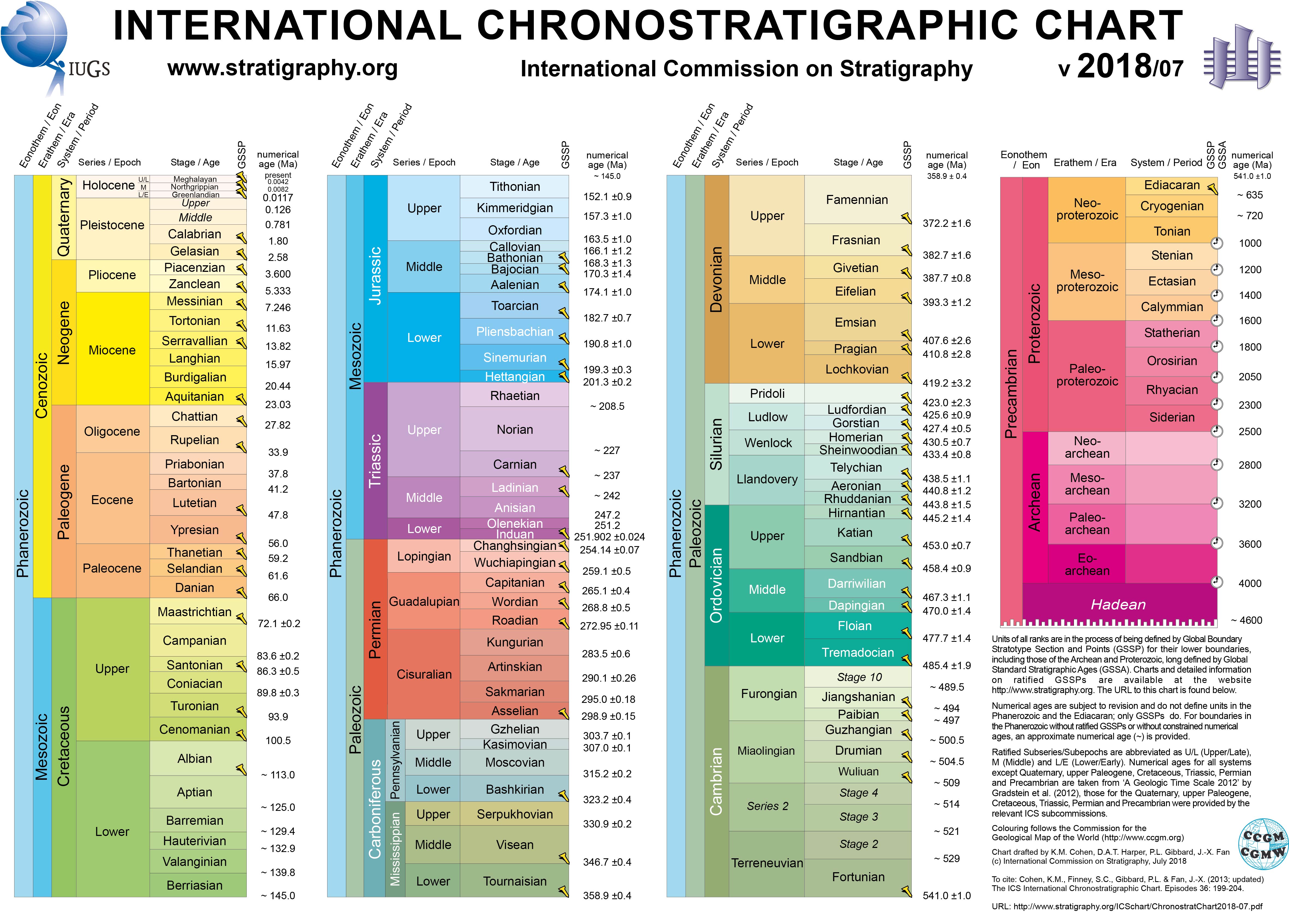

Die International Commission on Stratigraphy ICS ist die älteste und größte Untereinheit des Dachverbands aller nationaler geologischer Assoziationen und Vereinigungen weltweit, der International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS). Die IUGS ist also, salopp gesagt, so etwas wie die UN der Geologie. Es gibt ein Regelwerk, den sog. International Stratigraphic Guide; eine echte „legislative“ Befugnis gibt es allerdings natürlich nicht – die IUGS bzw. ICS kann keinen Geologen zwingen, die formalisierte Definition der erdgeschichtlichen (chronostratigraphischen) Einheiten zu übernehmen. Es ist aber guter Usus und macht viel Sinn, sich daran zu halten. Auch wenn das Ganze ein bürokratischer Vorgang ist, und sich nicht gerade viele Kollegen darum reißen, in den jeweiligen Subkommissionen der ICS (etwa zur Jurazeit oder zur Quartärzeit) zu sitzen und dies alles abzuwägen und zu diskutieren, ist allgemein akzeptiert, dass es Sinn macht, sich an diese “Chronostratigraphic Chart” zu halten, denn ein Kollege in China oder eine Kollegin in Brasilien sollte dasselbe unter dem Kambrium, dem Kimmeridgium, dem Quartär oder eben dem mittleren Holozän verstehen wie ich hier in Deutschland – und in Zukunft ggf. dann halt auch unter dem Anthropozän, sofern diese potentielle Epoche formalisiert werden sollte. In diesem Sinne macht es also sehr viel Sinn, diese drei Unterepochen nun fürs Holozän einzuführen, dadurch verbessern sich die Korrelationsmöglichkeiten und wir vergleichen nicht Äpfel mit Birnen (oder besser gesagt, alte Äpfel mit der neuen Ernte), sondern können das große Archiv der Erdgeschichte eben zeitscheibenbasiert und damit auch besser interdisziplinär, also zusammen mit Archäologen, Anthropologen, Frühgeschichtlern, Umwelthistorikern etc. zusammenarbeiten.

Die Untergrenze ist alles

Wichtig fürs Verständnis ist dabei: Solche erdgeschichtlichen chronostratigraphischen Einheiten werden immer nur durch die jeweilige Untergrenze definiert. Also konkret: die formale Untergrenze des Greenlandian definiert dessen Beginn und gleichzeitig den Beginn des Holozäns (konkret des unteren Holozäns), die formale Untergrenze des Northgrippian definiert den Beginn des Northgrippian (und damit des mittleren Holozäns) und stellt damit gleichzeitig die Obergrenze für das Greenlandian dar, die Untergrenze des Meghalayan ist gleichzeitig wiederum das Ende des Northgrippian sowie formaler Beginn des Meghalayan und des oberen Holozäns, eine Obergrenze dafür ist nicht formal definiert (Abb. 1). Die Grenzen im Quartär wurde bisher, dort wo sie bereits formalisiert sind – was für die gesamte Unterteilung des Pleistozäns übrigens noch nicht zutrifft -, an unterschiedlichen Lokalitäten in sedimentären Abfolgen formal definiert und zwar insbesondere auch anhand klimatischer „Geosignale“. Das Greenlandian (Eiskern NGRIP2) und das Northgrippian (Eiskern NGRIP1) wurden nun in zwei hinterlegten Grönland-Eiskernen definiert. Daraus erklären sich auch die Namen: Greenlandian bezieht sich allgemein auf Grönland, Northgrippian auf das Eiskernprojekt: North Greenland Ice Core Project. Neu ist, dass für das Meghalayan ein Tropfstein (genauer, ein von unten nach oben wachsender Stalagmit) verwendet wurde, und zwar aus der Mawmluh Höhle in Meghalaya, Nordost-Indien. Sollte nun ein Anthropozän formal definiert werden, wird dies wiederum entlang der Untergrenzendefinition sein, dazu existieren bereits publizierte Vorschläge (etwa in Waters et al. 2016 sowie in unserer aktuellen Diskussion zum Auffinden des besten Standardprofils sowie weiterer Hilfsprofile, Waters et al. 2018), aber noch gibt es keinen formalen Vorschlag (siehe dazu unten). Die Definition der holozänen stratigraphischen, basierend auf den jeweiligen Untergrenzen schließt also die Etablierung eines ebenfalls auf diese Weise – also durch eine Untergrenze – definierten Anthropozäns ganz und gar nicht aus.

Kriterien zur Definition

Was sind nun die Kriterien für die Definition der neuen formalen Einheiten? In der relativen Kürze des Quartärs hat sich evolutionär bei den Organismen eher zu wenig getan, als dass sie sehr gut als “Leitfossilien” verwendet werden könnten. Eher schon wäre das Wegfallen von Organismen nachweisbar, dies wird zur Definition etwa des basalen Quartär auch eingesetzt (offensichtliches Aussterben einiger “Nannofossilien”), allerdings ist dies ein negatives Kriterium, welches teilweise auch durch fehlende Erhaltung verursacht sein könnte – so unglaublich oft findet man auch klassische Leitfossilien, etwa die Ammoniten aus dem Paläozoikum und Mesozoikum nicht, daher sind positive Nachweise grundsätzlich viel angebrachter. Fürs Quartär verwendet man daher schon lange auch andere Proxies, wie magnetische Polaritätschronozonen sowie andere, umweltbasierte Geokriterien, um anhand natürlicher Schwankungen von Klima- und Umweltparameter Untergrenzen zu definieren. Dies gilt auch für die Untergrenze des Holozän (= Untergrenze des Greenlandian: plötzlicher Temperaturanstieg nach der letzten Eiszeit), wie auch für die Basis des Northgrippian, bei der durch das eventartige Auslaufen riesiger Schmelzwasserstauseen auf der Nordhemisphäre in die Meere zu völlig veränderten Strömungen v.a. im Nordatlantik und so zu einem starken Abkühlungsereignis führten, welches im Eiskern anhand von Sauerstoffisotpen und anderen Isotopen nachweisbar ist, aber etwa auch in Baumringen aus Deutschland oder in Seesedimenten des Ammersees und insgesamt weltweit identifizierbar ist (siehe hierzu Walker et al. 2012). Vermutlich hat diese Abkühlung beim Mensch zu einem weiteren Rückgang der Jäger- und Sammlertätigkeit beigetragen, jedenfalls koinzidiert der Beginn des Northgrippian mit einer sehr raschen Ausweitung des Neolithischen Transformation (also des Sesshaftwerdens) im mediterranen Bereich und in Teilen von Südost-Europa, Anatolien, Zypern und dem nahen Osten (cf. Walker et al. 2012). Die Untergrenze des Meghalayan ist ebenfalls mit Hilfe von Sauerstoffisotpen festgelegt, das Alter wurde mit der Uran/Thorium-Methode bestimmt. Dort ist ein insbesondere in niederen Breiten auftretender Aridisierungsimpuls, der ebenfalls mit einer Abkühlung verbunden war, besonders gut identifizierbar, weshalb eben kein Eiskern, sondern dieser subtropische Stalagmit zur Definition verwendet wurde. Aber auch hier ist der klimatische Event quasi weltweit durch verschiedene Methoden nachweisbar. Die auslösenden Ursachen für die Klimaveränderung sind eher noch ungenügend erforscht, Walker et al. 2012 führen eine mögliche Südwärtsverlagerung der innertropischen Konvergenzzone an, die auch den Beginn des recht regelmäßigen Auftretens von El Niños (ENSO) bedingt haben könnte. Auch hier haben die Klimaveränderungen eine deutliche, negative Auswirkung auf die Menschheit gehabt, so wird diskutiert ob dies nicht den Untergang einiger Hochkulturen ausgelöst haben könnte. Hierzu existieren aber sehr unterschiedliche Meinungen, vermutlich waren die Klimaveränderungen durchaus mit beteiligt, aber nicht die alleinige Ursache.

Holozän-Anthropozän-Gemeinsamkeiten

Gemeinsamkeiten zwischen den holozänen Untereinheiten und dem – bislang noch nicht formal definierten – Anthropozän wären eine deutliche Verzahnung von Erdsystem und menschlichen Gesellschaften, der kategoriale Unterschied wäre allerdings, dass im Holozän natürliche Umweltschwankungen den Hauptfaktor darstellen (auch wenn die Anteile menschengemachter Einflüsse zunehmen), während im Anthropozän eben der Mensch die Umweltveränderungen ganz wesentlich bedingt und damit auch die Geosignale menschengemacht sind. Die gute, nun hochauflösende chronostratigraphische Untergliederung des Holozäns – mit den jeweils basalen Klimawandelereignissen von nur wenigen 100en von Jahren, erlaubt eine immer bessere Analyse des zunehmenden, aber diachronen und regional sehr heterochronen Einfluss des Menschen auf das Erdsystems, bis dieser dann beginnend mit der Basis des – noch informellen – Anthropozäns in der Mitte des 20. Jahrhundert kulminiert.

OK, wenn dies so ist – so mögen nun manche denken – warum ist dann das Anthropozän nicht gleich mitdefiniert worden? Ist das Anthropozän, nachdem es in dieser Chart nicht auftaucht, nicht doch gleich von der ICS/IUGS “abgeschossen” worden? Eine derartige Einschätzung könnte auch noch dadurch gespeist werden, dass in einer ersten IUGS-Twitter-Verlautbarung das Meghalayan im Jahr 1950 aufhörte (siehe hier, inzwischen korrigiert) – sollte hier das Anthropozän noch Platz haben? – dies aber dann wieder revidiert wurde und in der Chart am Top des Meghalayan ja tatsächlich auch “present” steht? Geht da die Kluft quer durch die IUGS/ICS?

Was heißt heute “heute”?

Dazu muss man folgendes wissen: “before present” bedeutete geologisch betrachtet früher immer: vor 1950 n.Chr.. Das wurde so definiert, denn man brauchte, gerade auch für die absoluten Altersdatierungen, insb. mit C14-Methoden immer einen Referenzpunkt (wobei natürlich bei Millionen von Jahren zurückliegenden erdgeschichtlichen Altern dieser Referenzpunkt unerheblich ist, bei Quartär- oder gar Holozän-Altern aber dann eben doch wesentlich). Zum Jahrtausendwechsel wurde der Referenzpunkt für “before present” neu auf das Jahr 2000 n.Chr. festgelegt. Damit es nicht zu Verwirrungen kommt, soll man aber immer dazu sagen/schreiben b2k (before 2kiloyears). Im Tweet der IUGS kam dann offensichtlich dieser Referenzpunktfehler rein (vielleicht lag es daran, dass in der Karte als Obergrenze des Känozoikums weiterhin “present” und nicht b2k gedruckt ist?). Tatsächlich richtig ist allerdings für alle drei Alter, dass sie b2k-definiert sind, also Grenze zum Greenlandian: 11.700 Jahre b2k; zum Northgrippian: 8236 Jahre b2k und zum Meghalayan: 4250 Jahre b2K (siehe dazu die aktuelle Meldung der ICS/SQS hier).

Warum muss das nun so lange dauern, ist dies nicht doch ein Signal, dass man die Anthropozän-Diskussion vielleicht aussitzen will?

Nein, ganz und gar nicht. Derartiges für alle Geologen dieser Welt nachvollziehbar und möglichst akzeptabel, also auch verwendungsfähig zu machen zu machen, ist ein langwieriger Prozess, und augenzwinkernd gesagt: es könnte sogar sein, dass wir mit der Anthropozän-Definition einen Geschwindigkeitsreport brechen. Schauen wir erst mal aufs Holozän: Den Vorschlag, von der Lyell’schen Bezeichnung “Recent” (für die nacheiszeitliche Zeit) wegzukommen (später auch als Postglacial informell bezeichnet) und dies Holozän (das gänzlich Neue) zu nennen, wurde von Paul Gervais in den Jahren 1865-67 mehrfach gemacht. Immerhin gab der 3. Geologische Kongress in London im Jahr 1885 eine positive Empfehlung dazu ab. Formalisiert und danach breit akzeptiert wurde dies allerdings erst 1967/68 durch die USGS (der Vorläuferorganisation der IUGS), erst dann war das rezent formell weg und das Holozän formell da, obwohl es auch zuvor bereits in Gebrauch war (siehe hier).

Noch krasser steht es um die Definitionen von Tertiär und Quartär. Seit 1978 gab es Vorschläge, diese Begriffe zugunsten von Paläogen und Neogen abzuschaffen (Paläogen entsprach dem Alttertiär, Neogen dem Jungtertiär und Quartär; Pleistozän und Holozän würden als Epochen des Neogens aber Bestand haben). Ich habe mit dieser Verunsicherung mein Geologiestudium betrieben (von 1975-1980), ich hörte sowohl von Tertiär und Quartär als auch vom Paläogen und Neogen). 2004 wurde die Abschaffung von Tertiär und Quartär tatsächlich formal beschlossen, dies sollte allerdings erst 2008 effektiv werden. So ist heute das Tertiär formal abgeschafft (wie auch die aktuelle Chart zeigt, s. Abb. 2), aber 2005 gab es einen weiteren formalen Beschluss, zumindest das Quartär doch nicht abzuschaffen, wodurch auch das Neogen kürzer wurde (s.Abb. 1). Damit aber nicht genug, 2008 wurde beschlossen, die Quartärgrenze nach unten zu verlagern, genauer gesagt, das Gelasium, vormals Pliozän, nun dem Pleistozän zuzurechnen. Damit veränderte sich die Untergrenze des Quartärs von 1,8 Millionen Jahren vor heute auf 2,588 Millionen Jahre vor heute (genauer b2K). Damit gilt heute die Abfolge Paläogen, Neogen, Quartär.

Wer meinen sollte, dies sei ein Spezifikum des Quartärs, irrt. Selbst die Untergrenze der Kreide ist bis heute nicht formal definiert. Ich arbeitete mein Geologenleben lang viel im Oberjura, genauer in Oxfordium, Kimmeridgium und Tithonium, bis heute sind diese sehr geläufigen Einheiten ebenfalls noch nicht formal definiert. Etliche Untereinheiten des Pleistozän übrigens auch nicht. Dafür wurden nun mit der neuen Chart nicht nur die bislang informellen und eben dadurch auch unterschiedlich gebrauchten Untereinheiten des Holozän formalisiert, sondern auch einiges im Kambrium (genauer: die Wuliuan Stage und die Miaolingian Series, mit Typusprofilen in China). Schon in der neuen Chart dargestellt, aber erst in ein paar Tagen formal ratifiziert wird das Sakmarium aus dem Perm. Mit dem Begriff bin ich eigentlich aufgewachsen, aber er war immer informell – das war mir gar nicht mehr bewusst. Fürs Anthropozän bedeutet dies, dass man auch im geologischen Kontext bereits jetzt gerne damit arbeiten kann, also keinesfalls eine Regelverletzung begeht, aber es ist eben noch nicht formalisiert, und tatsächlich könnte der Beschluss kommen, dies nicht zu formalisieren, doch die Wahrscheinlichkeit dass das Anthropozän formalisiert wird, ist deutlich höher, zumindestens nach meiner Einschätzung.

Übrigens erscheinen Updates der Geological Timescale oft mehrfach im Jahr. Es werden dann oft neue Datierungen eingetragen, aber auch wie jetzt eben neu formalisierte Namen. Die aktuelle Version heißt 2018/07 (Abb. 2), zuvor gab es 2017/02 und 2016/04 (für ein Gesamtverzeichnis und Downloadmöglichkeit aller früherer Version siehe hier). Das Herausgeben einer neuen Chart ist also nun wirklich nicht der zeitliche Engpass 😉

Wie läuft die Formalisierung ab?

Dies kann auf der Webseite der ICS im Detail nachgelesen werden. Ich nehme mal das Beispiel für die Holozän-Untergliederung. Zuerst gab es eine Arbeitsgruppe, die mit der zuständigen Subkommission für Quartäre Stratigraphie (SQS) der ICS noch nichts zu tun hatte, bald aber ging die SQS auf diese Gruppe (namens Working Group of INTIMATE, mit INTIMATE für Integration of ice-core, marine and terrestrial records) zu und setzte sie formell als WG der SQS ein. Sie hatte zu prüfen, ob eine genaue Definition für eine Holozän-Untergliederung Sinn machen würde und wenn ja, wie diese Grenzen (und damit die entsprechenden Einheiten) definiert werden könnten. Die Diskussion, ein Holozän einzuführen zog sich insgesamt über mehrere Dekaden, aber 2012 erschien das hier bereits mehrfach erwähnte Discussion paper von Walker et al. 2012 dazu. Mike Walker war Leiter dieser SQS-Arbeitsgruppe. Dieses Paper sollte von der Community weltweit kommentiert werden, was auch passiert ist, danach dauerte der Formalisierungsprozess bis zur Ratifizierung eben noch bis zum 14. Juli 2018. Dazu notwendig waren ein formaler Vorschlag der WG zur Formalisierung an die SQS, diese stimmt ab, danach noch die ICS, danach noch der executive Board der IUGS. Das Abstimmungsprocedere kann auch mehrfach hin- und hergehen, falls nachgearbeitet werden soll, es kann aber auch an jeder Stelle zu einer Ablehnung führen, das wäre es dann gewesen. Aber die Holozän-Untereinheiten sind nun ja formalisiert und sollten Bestand haben. Nach einer Gewöhnungszeit wird die globale Community sicherlich die neuen Namen verwenden, denn die Vorteile sind klar ersichtlich.

Übrigens haben Walker et al. 2012 in ihrem Discussion-Paper schon das Anthropozän aufgeführt, sie schreiben dazu (Zitat):

The Anthropocene

It has been suggested that the effects of humans on the global environment, particularly since the Industrial Revolution, have resulted in marked changes to the Earth’s surface, and that these may be reflected in the recent stratigraphic record (Zalasiewicz et al., 2008). The term ‘Anthropocene’ (Crutzen, 2002) has been employed informally to denote the contemporary global environment that is dominated by human activity (Andersson et al., 2005; Crossland, 2005; Zalasiewicz et al., 2010), and discussions are presently ongoing to determine whether the stratigraphic signature of the Anthropocene is sufficiently clearly defined as to warrant its formal definition as a new period of geological time (Zalasiewicz et al., 2011a,b). This is currently being considered by a separate Working Group of the SQS led by Dr Jan Zalasiewicz and, in order to avoid any possible conflict, the INTIMATE/SQS Working Group on the Holocene is of the view that this matter should not come under its present remit. Nevertheless, we do acknowledge that although there is a clear distinction between these two initiatives, the Holocene subdivision being based on natural climatic/environmental events whereas the concept of the Anthropocene centres on human impact on the environ- ment, there may indeed be areas of overlap, for example in terms of potential human impact on atmospheric trace gas concentrations not only during the industrial era, but also perhaps during the Middle and Early Holocene (Ruddiman, 2003, 2005; Ruddiman et al., 2011). However, it is the opinion of the present Working Group that the possible definition of the Anthropocene would benefit from the prior establishment of a formal framework for the natural environmental context of the Holocene upon which these, and also other human impacts, may have been superimposed. (Zitat Ende).

Und wie läuft es nun bei der geologischen Anthropozän-Definition? Wiederum gab es eine Initiative einer externen Gruppe (hervorgegangen aus verschiedenen Treffen in der Royal Society London). Seit 2008 existiert diese Gruppe in erweiterter Form als von der SQS eingesetzten Working Group on the “Anthropocene” (AWS). Wiederum ist der Auftrag a) zu testen, ob es Sinn macht, ein Anthropozän zu definieren, und b) falls ja, wo die diese Untergrenze zu ziehen wäre und c) wie sie definiert werden kann. Diese Arbeiten sind langwierig, wir schrieben etliche konzeptionelle Papers und kamen zu dem Schluss, dass eine Grenzziehung in der Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts am sinnvollsten wäre (siehe dazu viele Beiträge in diesem Block). Wir diskutierten auch, ob – im Sinne einer raschen Formalisierung – die Definition nur durch ein bestimmtes zeitliches Datum (sogenannter GSSA-Prozess, Global Standard Stratigraphic Age) sinnvoll wäre, und warfen hier den Zeitpunkt des ersten Atombombenversuches in Alamo Gordo (16. Juli 1945) in den Ring (Zalasiewicz et al. 2015). Die Diskussion außerhalb und innerhalb der SQS ergab, dass eine “klassische” GSSP-Definition (durch eine Global Stratigraphic Section and Point, sog. “Golden Spike”) besser geeignet sei, auch um höhere Akzeptanz zu erreichen. Seitdem stellen wir Geosignal-Kriterien für die Untergrenzenerkennung zusammen (siehe z.B. Zalasiewicz et al. 2016, Waters et al. 2016, Zalasiewicz et al,. 2017) und haben vor kurzem eine umfassende Sichtung der Möglichkeiten der weltweiten synchronen Grenzziehung durch einen GSSP und weiteren “auxiliary sections” in einer umfassenden Arbeit zur Diskussion vorgestellt (Waters et al. 2018). Wir haben auch mehrfach Bezug auf die Walker et al. 2012-Arbeit genommen und sehen weiterhin, und in Übereinstimmung mit der Walker-WG, dass Holozän und Anthropozän sehr unterschiedlich, aber eben auch komplementär sind. Wir sind derzeit dabei, noch weitere Kandidaten für mögliche “Golden Spikes” zu untersuchen, und zwar in Kooperation mit Kollegen weltweit (also nicht nur innerhalb der AWG) und werden dazu noch etliche Treffen und weitere Studien benötigen. Ein umfassender Statusbericht ist in Buchform im Druck (Zalasiewicz et al. 2018). Wir hoffen, dass wir in wenigen Jahren ein abschließendes Diskussionspapier veröffentlichen können und dran anschließend ggf. einen formalen Vorschlag an die SQS/ICS/IUGS stellen werden, der dann, ganz wie oben für das Holozän angegeben auch formal behandelt wird. Es wird also noch einige Jährchen dauern, bis das Anthropozän auch formal in der Stratigraphic Chart auftaucht, oder eben auch nicht. Dass das Anthropozän-Assessment dennoch auch ohne bislang formale Definition bereits große wissenschaftliche und gesellschaftliche Wirkung zeigt, versuche ich ja auch immer wieder u.a. auf diesem Blog aufzuzeigen. Wir leben also formell derzeit im Quartär, genauer im Holozän, noch genauer im Meghalayan, informell sollte aber, anbetracht der menschengemachten Eingriffe in das Erdsystem und der daraus resultierenden Veränderung der Kreislauf-, Verwitterungs-, Transport- und Sedimentationsprozesse, aber auch der Eingriffe in die Biosphäre und den daraus resultierenden Veränderungen der Sedimente klar sein, dass wir aus dieser Sicht betrachtet durchaus bereits in einer anderen Zeit leben, dem Anthropozän. Wer es schafft, ganze Berge zu kappen, neue Täler zu schneiden, Seen auslaufen zu lassen oder neu anzulegen, die Organismen zu dominieren, das Klima zu ändern und den Meeresspiegel steigen zu lassen, wird nicht darüber verwundert sein, dass sich dies auch geologisch-stratigraphisch dauerhaft niederschlägt.

Literatur:

a) die oben mehrfach erwähnte Arbeit von Walker et al. (2012):

M. J. C. Walker M. Berkelhammer S. Björck L. C. Cwynar D. A. Fisher A. J. Long J. J. Lowe R. M. Newnham S. O. Rasmussen H. Weiss (2012): Formal subdivision of the Holocene Series/Epoch: a Discussion Paper by a Working Group of INTIMATE (Integration of ice‐core, marine and terrestrial records) and the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (International Commission on Stratigraphy).- Journal of Quaternary Science, 27 (7), 649-659. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2565

b) oben zitierte sowie weitere aktuelle Publikationen aus der Working Group on the “Anthropocene” (unvollständig, chronologisch rückwärts geordnet):

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C., Williams, M. & Summerhayes, C. (eds) (2018, in press): The Anthropocene as a geological time unit: an analysis, Cambridge University Press. Mit Beiträgen von Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Waters, Mark Williams, Colin Summerhayes, Martin Head, Reinhold Leinfelder, Jacques Grinevald, John McNeill, Naomi Oreskes, Will Steffen, Scott Wing, Phil Gibbard, Davor Vidas, Trevor Hancock, Anthony Barnosky, Bob Hazen, Andy Smith, Neil Rose, Agnieszka Gałuszka, An Zhisheng, Simon Price, Daniel deB. Richter, Sharon A Billings, James Syvitski, Ian Wilkinson, David Aldridge, Valentin Bault, Peter Haff, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Ian Fairchild, Michael Wagreich, Irka Hajdas, Catherine Jeandel, Alejandro Cearreta, Eric Odada, Erich Draganits, Matt Edgeworth, J. R. McNeill (> Info)

Colin N. Waters, Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Summerhayes, Ian J. Fairchild, Neil L. Rose, Neil J. Loader, William Shotyk, Alejandro Cearreta, Martin J. Head, James P.M. Syvitski, Mark Williams, Anthony D. Barnosky, An Zhisheng, Reinhold Leinfelder, Catherine Jeandel, Agnieszka Galuszka, Juliana A. Ivar do Sul, Felix Gradstein, Will Steffen, John R. McNeill, Scott Wing, Clement Poirier, Matt Edgeworth (2018): Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the Anthropocene Series: Where and how to look for potential candidates. . Earth Science Reviews, 178, 379-429, DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.12.016 (online first: accepted ms version, EARTH 2557: Dec. 30, 2017; final version: Mrch 2, 2018)

Colin N. Waters, Michael Wagreich, Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Summerhayes, Ian J. Fairchild, Neil L. Rose, Neil J. Loader, William Shotyk, Alejandro Cearreta, Martin J. Head, James P.M. Syvitski, Mark Williams, Michael Wagreich, Anthony D. Barnosky, An Zhisheng, Reinhold Leinfelder, Catherine Jeandel, Agnieszka Galuszka, Juliana A. Ivar do Sul, Felix Gradstein, Will Steffen, John R. McNeill, Scott Wing, Clement Poirier, Matt Edgeworth (2018):Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the Anthropocene Series: Where and how to look for potential candidates. Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 20, EGU2018-4590, 2018, European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2018, SSP2.1, online-Version

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters, Colin P. Summerhayes, Alexander P. Wolfe, Anthony D. Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Paul Crutzen, Erle Ellis, Ian J. Fairchild, Agnieszka Galuszka, Peter Haff, Irka Hajdas, Martin J. Head, Juliana A. Assunção Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, John R. McNeill, Cath Neal, Eric Odada, Naomi Oreskes, Will Steffen, James Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams (2017): The Working Group on the Anthropocene: Summary of evidence and interim recommendations.- Anthropocene doi:10.1016/j.ancene.2017.09.001

Zalasiewicz, J, Waters, CN, Wolfe, A P, Barnosky, AD, Cearreta, A, Edgeworth, M, Ellis, E, Fairchild,IJ, , Gradstein, FM, Grinevald, J, Haff, P, Head, MJ, Ivar do Sul, J, Jeandel, C, Leinfelder, R, McNeill, JR,Oreskes, N, Poirier, C, Revkin, A, Richter, DB, Steffen, W, Summerhayes, C, Syvitski, JPM, Vidas, D, Wagreich, M, Wing, S & Williams, M(2017), Making the case for a formal Anthropocene Epoch: an analysis of ongoing critiques, Newsletters on Stratigraphy, 50(2), 205-226, Online First DOI: 10.1127/nos/2017/0385 22 Mrch 2017,

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters & Martin Head (on behalf of all members of the Anthropocene Working Group) (2017): Correspondence: Anthropocene: its stratigraphic basis.- Nature, 541, p. 289, doi: 10.1038/541289b

Jan Zalasiewicz, Will Steffen, Reinhold Leinfelder, Mark Williams & Colin M. Waters (2016): Petrifying earth processes.- In: Clark, Nigel (ed), Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(3-2), #-# (Sage Journals), online first (13 March 2017): DOI: 10.1177/0263276417690587, printed vers. May 2017

Jan Zalasiewicz, Mark Williams, Colin N Waters, Anthony D Barnosky, John Palmesino, Ann-Sofi Rönnskog, Matt Edgeworth, Cath Neal, Alejandro Cearreta, Erle C Ellis, Jacques Grinevald, Peter Haff, Juliana A Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, John R McNeill, Eric Odada, Naomi Oreskes,Simon James Price, Andrew Revkin, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, Davor Vidas, Scott Wing, Alexander P Wolfe (2017): Scale and diversity of the physical technosphere: A geological perspective.- The Anthropocene Review, 4 (1), 9-22 doi:10.1177/2053019616677743 (online first publ.date Nov. 28, 2016)

Waters, C.N., Zalasiewicz, J., Barnosky, A.D., Cearreta, A., Edgeworth, M., Fairchild, I.J., Galuszka, A., Ivar do Sul, J.A., Jeandel, C., Leinfelder, R., Odada, E., Oreskes, N., Price, S.J., Richter, D.deB., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J.P., Wagreich, M., Williams, M., Wing, S., Wolfe, A.P. & An Zhisheng (2016): Assessing Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) candidates for the Anthropocene.- Paper # 2914, Abstract 35th International Geological Congress, Cape Town, South Africa 27th August – 4th September 2016. see here

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C.N., An, Z., Barnosky, A.D., Cearreta, A., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E.C., Fairchild, I.J.., Gałuszka, A., Haff, P.K., Ivar do Sul, J.A., Jeandel, C., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J.R., Odada, E.., Oreskes, N., Price, S.J., Richter, D. deB., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J.P., Wagreich, M., Williams, M., Wing, S. & Wolfe, A.P (2016): The Anthropocene: overview of stratigraphical assessment to date.- Paper # 3966, Abstract 35th International Geological Congress, Cape Town, South Africa 27th August – 4th September 2016. see here

Steffen, W., Leinfelder, R., Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Williams, M., Summerhayes, C., Barnosky, A. D., Cearreta, A., Crutzen, P., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E. C., Fairchild, I. J., Galuszka, A., Grinevald, J., Haywood, A., Sul, J. I. d., Jeandel, C., McNeill, J.R., Odada, E., Oreskes, N., Revkin, A., Richter, D. d. B., Syvitski, J., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Wing, S. L., Wolfe, A. P. and Schellnhuber, H.J. (2016): Stratigraphic and Earth System Approaches to Defining the Anthropocene.- Earth’s Future, 4 (8), 324-345, DOI:10.1002/2016EF000379 (publ. Jul 20, 2016)

Williams, M., Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Edgeworth, M., Bennett, C., Barnosky, A. D., Ellis, E. C., Ellis, M. A., Cearreta, A., Haff, P. K., Ivar do Sul, J. A., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J. R., Odada, E., Oreskes, N., Revkin, A., Richter, D. d., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J. P., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Wing, S. L., Wolfe, A. P. and Zhisheng, A. (2016): The Anthropocene: a conspicuous stratigraphical signal of anthropogenic changes in production and consumption across the biosphere.- Earth’s Future, 4, 34-53 (Wiley) doi: 10.1002/2015EF000339

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Patricia L. Corcoran, Anthony D. Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Agnieszka Galuszka, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, J.R. McNeill, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams, Alexander P. Wolfe & Yasmin Yonan (2016): The geological cycle of plastics and their use as a stratigraphic indicator of the Anthropocene.- Anthropocene, 13, 4–17, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2016.01.002 (Elsevier)

Colin N. Waters,Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Summerhayes, Anthony D. Barnosky, Clément Poirier, Agnieszka Galuszka, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Erle C. Ellis, Michael Ellis, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, J. R. McNeill, Daniel de B. Richter, Will Steffen, James Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams, An Zhisheng, Jacques Grinevald, Eric Odada, Naomi Oreskes, Alexander P. Wolfe (2016): The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene.- Science 8 January 2016: Vol. 351 no. 6269 DOI: 10.1126/science.aad2622

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N Waters, Anthony D Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Erle C Ellis, Agnieszka Galuszka, Philip L Gibbard, Jacques Grinevald, Irka Hajdas, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, JR McNeill, Clément Poirier, Andrew Revkin, Daniel deB Richter, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, James PM Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams and Alexander P Wolfe (2015): Colonization of the Americas, “Little Ice Age” climate, and bomb- produced carbon: Their role in defining the Anthropocene – The Anthropocene Review August 2015 2: 117-127, doi:10.1177/2053019615587056

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N Waters, Anthony D Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Erle C Ellis, Agnieszka Galuszka, Philip L Gibbard, Jacques Grinevald, Irka Hajdas, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, JR McNeill, Clément Poirier, Andrew Revkin, Daniel deB Richter, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, James PM Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams & Alexander P Wolfe (2015): Corresponcence: Epochs: Disputed start dates for the Anthropocene.- Nature, 520, p. 436, doi:10.1038/520436b

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C.N., Williams, M., Barnosky, A.D., Cerreata, A., Crutzen, P., Ellis, E., Ellis, M.E., Fairchild, I.J., Grinevald, J., Haff, P.K., Hajdas, I., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J., Odada, E.O., Poirier, C., Richter, D., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J.P.M., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Wing, S.L., Wolfe, A.P., An, Z. & Oreskes, N. Published online. When did the Anthropocene begin? A mid-twentieth century boundary is stratigraphically optimal. Quaternary International,, 383 (2015), 196-203.

Online first 12.1.2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2014.11.045

c) weitere aktuelle Arbeiten des Autors (auch) zum Anthropozän finden sich unter reinhold-leinfelder.de auf der Eingangsseite.

Fassung vom 20.7.2018,

einige Korrekturen und kleinere stilistische Änderungen, sowie Einfügen von Abb. 2 sowie der Literaturzitate vom 21.7.2018

Nachtrag vom 25.7.2018: Ein Interview mit mir zum Thema gab es am 24.7.2018 in Deutschlandfunkt, Forschung aktuell, nun in der Mediathek

Nachtrag vom 30./31.7.2018: editierte englisch-Übersetzung, siehe Kommentarfunktion bzw. direkt hier: https://tinyurl.com/meghalayan-commentary-RL

Hier wurde das Bednarikozän noch nicht erwähnt, das im Jahre 1946 begonnen hat.

Danke, nehme ich in die Liste mit auf 😉 Es gäbe auch noch konkurrierende Vorschläge wie Pyrozän, Plastizän, Homogenozän, Kapitalozän, Knetozän, Plantationozän, Chtuluzän usw usw. Vielleicht sollten wir einfach XYpsilonozän nehmen? Aber dazu nicht heute, sondern vielleicht demnächst mal in nem weiteren Beitrag.

Das Anthropozän macht Sinn, wobei der Sinn im dankenswerterweise bereit gestellten WebLog-Eintrag neunfach referenziert worden ist, es macht sozusagen Sinn Sinn zu machen, also das “gute alte” Anthropozän.

Weitere Aufschlüsselung / Kategorisierung macht womöglich auch Sinn, und -Hey, wer glaubt nicht an das Dominium Terrae?-, abär der Webbaer will sich hier nicht sonderlich einmischen,

MFG + weiterhin viel Erfolg,

Dr. Webbaer

Das Anthropzän könnte doch sogar das Holozän ablösen anstatt nur der Nachfolger der Unereinheit Meghalayan zu sein. Das Holozän wäre dann einfach eine Warmzeit, das Anthropozän ein Zeitabschnitt, in dem die Eiszeit unterbrochen ist.

“Das Anthropozän macht Sinn, …”

Nur in der englischen Sprache.

Pardon, das verstehe ich jetzt nicht ganz. Meinen Sie, man sollte immer Anthropocene sagen? Die sonstigen Epochen/Serien des Quartärs, also z.B. Pliocene, Pleistocene, Holocene heißen in der deutschen Anpassung immer schon Pliozän, Pleistozän, Holozän. Deswegen in Konsequenz auch Anthropozän. cene bzw zän kommt vom altgriechischen καινός kainós „neu“.

@Reinhold Leinfelder: Peter Fasten meint mit “Das Anthropozän macht Sinn,..” Nur in der englischen Sprache, nicht den Begriff Anthropozän, sondern die Redewendung macht Sinn, eine Übersetzung von makes sense, deren Entsprechung im Deutschen ergibt Sinn ist.

Macht, ehm ergibt Sinn, oder so ähnlich 😉

Das hier ist die Wachstums-Konkurrenz zwischen

“hat Sinn” und “macht Sinn” im Ngram Viewer:

https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=hat+Sinn%2Cmacht+Sinn&year_start=1958&year_end=2008&corpus=20&smoothing=0&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Chat%20Sinn%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cmacht%20Sinn%3B%2Cc0

Unser Herr Dr. Leinfelder ist da seinerzeit mal mit gewissem “Bleiblatt” ein wenig ungut aufgestoßen, er hat sich in der Folge von bestimmten “Gags” distanziert und an der Sinnhaftigkeit der Begriffsbildung ‘Anthropozän’ gibt es heutzutage kaum Zweifel, vgl. :

-> http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-147013423.html

Das hier gemeinte Erkenntnissubjekt ist ‘parasitisch’ und auch gestalterisch, im Sinne des Anthropäzan.

Allerdings, allerdings, wird der Geologe (der Schreiber dieser Zeilen ist (auch) hier keine Fachkraft) noch besondere Nachweise des menschlichen Tuns auf der Erde erwarten, die die Erde besonders betreffen, diese erfolgen absehbarerweise nach und nach.

MFG + weiterhin viel Erfolg!

Dr. Webbaer (der sich vor einigen Jahren mal ernsthaft um Diskussionen zu bemühen hatte, in denen es um die Frage ging, ob sich Sinn ergibt oder gemacht wird, aus konstruktivistischer Sicht wird er gemacht)

*

Beiblatt

Der Vollständigkeit halber mit “hat Sinn, macht Sinn, Sinn hat, Sinn macht”:

(Die Invasion des “macht” beginnt um 1980.)

https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=hat+Sinn%2Cmacht+Sinn%2CSinn+hat%2CSinn+macht&year_start=1958&year_end=2008&corpus=20&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Chat%20Sinn%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cmacht%20Sinn%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2CSinn%20hat%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2CSinn%20macht%3B%2Cc0

Sehr hübsch beigebracht, Herr Bednarik, vielen Dank.

Sinn wird gemacht, insofern so wie auch das Konzept ‘Sinn’ gemacht ist, es steht ja nicht von Erkenntnissubjekten unabhängig sozusagen wie eine Sau auf dem Sofa.

Er ist ohne erkennenden Subjekten undenkbar.

Erst die Sprachlichkeit macht Sinn, ohne Sprache wäre sozusagen alles Nichts (dann aber nicht so genannt, weil diese Begrifflichkeit nicht bereit stünde).

Auf der von Ihnen dankenswerterweise beigebrachten Zeitskala aufgetragen kann sich Konstruktivismus wiederfinden.

Andere sehen’s anders und es gab hier zuvörderst, die Vergangenheitsform ist gemeint, böse Diskussionen : einstmals.

MFG + schöne Woche noch,

Dr. Webbaer

Translation (for original posting in german scroll up or click here).

Meghalayan or Anthropocene? Which geological period are we living in today?

By Reinhold Leinfelder

Greenlandian, Northgrippian, Meghalayan – what is that?

More or less excited contributions have been recently posted in the (social) media, referring to the the recent formalization of the new Holocene, hence of the the geological epoch following the last ice age. Until now the terms Early, middle and Late Holocene existed, but these were used informally and therefore also in a sometimes different way. Now there is a Greenlandian, Northgrippian and Meghalayan (using it in latinised geological customs, as used in Germany, these would be Greenlandium, Northgrippium and Meghalayum). (Formally these are on the scale of „stages“ (when looking at the sediments) or “ages“ when looking at time, but at the same time define the “subseries/subepochs” of the Holocene, but this might only interest specialists). The Greenlandian and thus the Holocene thus began, as aready acknowledged earlier, 11,700 years before “today”, the Northgrippian 8,200 years before “today” and the Meghalayan 4200 years before “today” (for the geological meaning of “today” see below).

Click here for Fig. 1

Fig. 1: The new geochronological subdivision for the Holocene, IUGS/ICS vers. 2018/7, for more details see text

Has the Anthropocene “died“?

So far so good, but does this mean that the Anthropocene has now been “abolished” or “rejected”? Some actually seem to suspect this. Others joke that this geological timetable would change names more often than the name of clubs in St. Pauli, Hamburg. Especially British and American media reported so far, partly also to alleged controversies, as did the Austrian Broadcast ORF and, IUGS, the responsible umbrella organization IUGS came up with some slightly misleading statements. I experienced requests from German media as well (being a member of the Working Group on the “Anthropocene” (AWG). So here’s a possibly necessary clarification.

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) is the oldest and largest body of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS). The IUGS is, to put it in a grossly simplified manner, something like the UN of geology. They published a set of rules, the so-called International Stratigraphic Guide; of course this does not imply a real “legislative” authority – the IUGS or ICS cannot force any geologist to adopt the formalised definition of geological (chronostratigraphic) units. But it is common practice, and makes a lot of sense, to stick to it. Even if the whole process is quite bureaucratic, and not many colleagues are keen to sit in such sub-commissions of the ICS (for example in sub-commissions for the Jurassic or Quaternary periods) to sort out and discuss all this, it is generally accepted that it makes sense, to adhere to this “Chronostratigraphic Chart“, because a colleague in China or a colleague in Brazil should understand the same as, say, Cambrian, Kimmeridgian, Quaternary or even the Middle Holocene as I here in Germany – and in the future if necessary. then also Anthropocene, if this potential epoch should be formalized. Under this view, it makes a lot of sense to introduce these three subepochs now for the Holocene, thereby improving the correlatibility in order not to compare apples with pears (or better said, old apples with the new harvest), but rather to improve working with the large archive of earth history by using a time-slice approach, to better integrate data under cooperation with archaeologists, anthropologists, environmental historians etc,

The lower boundary is what matters

Important for understanding the formal definition: Geological chronostratigraphic units are always defined only by their lower boundaries. To be precise: the formal lower boundary of the Greenlandian defines its beginning (and at the same time the beginning of the Holocene, specifically the lower Holocene), the formal lower boundary of Northgrippian defines the onset of the Northgrippian (and thus the middle Holocene) and thus represents the upper boundary for Greenlandian, the lower boundary of the Meghalayan is again serving as the upper boundary of the Northgrippian, and defines the formal onset of the Meghalayan and the upper Holocene. Thus, an upper limit for the Meghalayan/Upper Holocene is not formally defined and remains open (Fig. 1).

The boundaries for the Quaternary series and subseries, where they have already been formalized – which by the way does not yet apply to the entire subdivision of the Pleistocene – were formally defined at different localities in sedimentary sequences, in particular also based on climatic “geosignals”. The Greenlandian (ice core NGRIP2) and the Northgrippian (ice core NGRIP1) have now been defined in two Greenland ice cores. This explains the names: Greenlandian generally refers to Greenland, Northgrippian to the North Greenland Ice Core Project. New is that for the Meghalayan a dripstone (more precisely, a stalagmite growing from bottom to top) was used, namely from the Mawmluh cave in Meghalaya, north-east India. If an Anthropocene is now formally defined, this will again be based on a lower boundary definition. There already exist published proposals (e.g. in Waters et al. 2016 and in our current discussion on finding the best standard profile and other auxiliary profiles, Waters et al. 2018), but there is still no formal proposal yet (see below). The definition of the Holocene stratigraphy, based on its respective lower boundaries, thus does not at all exclude the formal establishment of an Anthropocene epoch, which also would be defined in an analogous way- i.e. by a lower boundary.

Criteria for definition

So what are the criteria for defining the new formal units? In the relative brevity of the Quaternary, evolutionary changes in the organisms have been mostly too minor to allow establishment of „Leitfossilien (stratigraphically „guiding fossils“). The disappearance of organisms actually would be detectable – and this is also used to define the base of the Quaternary (obvious extinction of some “nannofossils”), but this is a negative criterion, which could also be partly caused by lack of conservation – it is a geologist’s trouble that he/she often one does not find a classical Leitfossil, such as the ammonites from the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic, therefore positive evidence is much more appropriate. Therefore, other proxies have been used since long for the Quaternary They include magnetic polarity chronozones and other, environmentally-based geocriteria, to define lower limits on the basis of natural fluctuations in climate and environmental parameters. This also applies to the lower boundary of the Holocene (= lower limit of Greenlandian: a sudden rise in temperature after the last ice age), as well as to the lower boundary of the Northgrippian, where huge meltwater reservoirs on the northern hemisphere led to different current systems especially in the North Atlantic and thus caused to a distinct cooling event, which can be detected in the ice core using oxygen and other isotopes, but can likewise be identified in tree rings from Germany or in lake sediments of the Ammersee and throughout the world (see Walker et al. 2012).

Presumably this cooling has contributed to a further decline in human hunting and gathering: at least the beginning of the Northgrippian coincides with a very rapid expansion of the neolithic transformation (i.e. settlement) in the Mediterranean region and in parts of southeastern Europe, Anatolia, Cyprus and the Middle East (cf. Walker et al. 2012). The lower boundary of the Meghalayan is also determined by using oxygen isotopes, the absolute age was identified using the uranium/thorium method. At that time, an aridization pulse, especially in lower latitudes, which was also associated with a cooling pulse, is particularly well identifiable, which is why no ice core, but this subtropical stalagmite has been used for defining its lower boundary. But again, the climatic event can be identified worldwide by a various set of proxy methods. The causes of this climate change pulse have not yet been sufficiently studied, but Walker et al. 2012 point to a possible southward shift of the intra-tropical convergence zone, which could also have caused the beginning of the fairly regular occurrence of El Niños (ENSO). This relatively rapid climate change obviously has had a clear, negative impact on human societies, and the demise of some advanced civilizations in relation to this is much discussed. However, there are quite different opinions on this – it appears that climate changes was involved, but not the only cause for the demse

Holocene Anthropocene Commonalities

Common features of the Holocene subunits and the – not yet formally defined – Anthropocene would be a clear interlocking of the Earth system and human societies, but the categorical difference of both would be that natural environmental fluctuations have been the main factor in the Holocene (even if the proportions of human-made influences had been increasing), while in the Anthropocene, humans were the main cause of environmental changes and thus also the geosignals are anthropogenic.

The now improved time-resolution for the new chronostratigraphic subdivision of the Holocene – with respective basal climate change events of only a few hundred years – gives way to an improved analysis of the increasing, but diachronous, and regionally very heterochronous, influence of humanity on the entire Earth system, culminating in the base of the – still informal – Anthropocene in the mid20th century.

OK, if this is the case , why wasn’t the Anthropocene defined at once – as some may think? Hasn’t the Anthropocene been „killed“ by the ICS/IUGS, since it does not appear in this new chart? Such an assessment could also be nourished by the fact that the Meghalayan was first said to end in 1950, as was announced in a first IUGS tweet (<a href="https://twitter.com/theIUGS/status/1019546368971591680" target="extra"see here, now corrected). Was this 1950 line announced to still have room for the Anthropocene? But if so, why was it then revised again, and why does the new chart actually says „present“ at the top of Meghalayan, Is there a the split across the IUGS/ICS?

What does “today” mean geologically?

One must know the following: geologically speaking, “before present” always meant before 1950 A.D.. This was defined as follows, because of the necessity to have a reference point for absolute age dating, especially for C14 methods (- such a reference point is insignificant for geological dating rocks being many millions of years old, but essential for the much younger Quaternary and especially Holocene ages). At the turn of the millennium, the reference point for “before present” was redefined to the year 2000 AD. To avoid confusion, geologists should always say/write b2k (before 2kiloyears). In the original tweet of the IUGS obviously such a reference point error entered (maybe because the upper limit of the Cenozoic is still considered informally as “present” and not as b2k ). Correct is that all three ages are b2k-defined, i.e. border to Greenlandian: 11,700 years b2k; to Northgrippian: 8236 years b2k and to Meghalayan: 4250 years b2K (see the current ICS/SQS report here).

Why does this all take so long now, is this not a signal that IUGS may want to ride out the Anthropocene discussion?

No, not at all. To make such a process comprehensible and the outcome as acceptable and usable as possible for all geologists of this world, such an extended process is important, and with a twinkle of the eye: it could even be that we break a speed record with the Anthropocene definition. Let us first look at the Holocene: The proposal to get away from Lyell’s term “Recent” (later also informally called postglacial) and to name this the Holocene (translates in „the completely new“) was made by Paul Gervais several times in the years 1865-67. After all, already in 1885 the 3rd Geological Congress in London came up with a positive recommendation. However, this was formalised and then widely accepted only in 1967/68 by the USGS (the predecessor organisation of the IUGS), only then „the Recent“ has been formally abolished and the Holocene formally established, although it has been already in use before (see here).

The definition processes for the Tertiary and Quaternary are even more blatant. Since 1978 there have been proposals to abolish these terms in favour of Palaeogene and Neogene (Palaeogene corresponds to the former Tertiary, Neogene to the Upper Tertiary and the Quaternary; however, Pleistocene and Holocene would remain as epochs of the Neogene). I studied geology at university with this uncertainty (from 1975-1980), I heard about Tertiary and Quaternary as well as Palaeogene and Neogene). In 2004, the abolition of the Tertiary and Quaternary has in fact been formally decided, but should only become effective in 2008. Thus, today the Tertiary has been formally abolished (as the current chart also shows, see Fig. 2), but in 2005 there was another formal decision not to abolish at least the Quaternary, which also shortened the Neogene (see Fig. 1). But that was not all: in 2008 it has been decided to set the Quaternary boundary deeper, more precisely, at the beginning of the Gelasian, formerly part of the Pliocene, now belonging to the Pleistocene. Thus, the lower boundary of the Quaternary changed from 1.8 million years ago today to 2.588 million years before today (more precisely b2K).

Thus the formalized sequence today consists of the Palaeogene, Neogene, and Quaternary.

Click here for Fig. 2

Fig. 2: The current chronostratigraphic map of the ICS/IUGS, Vers. 2018/7

Who thinks that this is a very specific feature of the Quaternary is mistaken. Even the lower boundary of the Cretaceous has not yet been formally defined. I myself worked a lot during my geological life in the Upper Jurassic, more precisely in the Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian and Tithonian – until today these very common units have also not yet been formally defined. As aren’t a a number of Pleistocene subdivisions. By the way, the new chart has now formalized not only the previously informal and therefore also differently used subunits of the Holocene, but also some in the Cambrian (more precisely: the Wuliuan Stage and the Miaolingian Series, with reference sections in China). Already represented in the new chart, but only becoming formerly ratified within in a few days is the Sacmarium from the Permian. I actually grew up with the term, but it was always informal – I was no longer even aware of that. For the Anthropocene this means that geologists can already work with it in a geological context, i.e. they do not commit a rule violation at all, but it has not yet been formalised, and in fact it could be decided not to formalise it, but the probability that the Anthropocene will be formalised is considerably higher, at least in my opinion.

By the way, updates of the Geological Timescale often appear several times a year. Often age dates are then redefined, but also, as for the recent new version, newly formalised names are introduced. The current version is 2018/07 (fig. 2), before there were 2017/02 and 2016/04 (for a complete directory and download of all earlier versions see here). So releasing a new chart is really not the time bottleneck.

How does formalisation work?

This can be studied in detail on the ICS website. Let me take the example of the Holocene subdivision. First there was a working group which had nothing to do with the responsible sub-commission for quaternary stratigraphy (SQS) of the ICS, but soon the SQS approached this group (called Working Group of INTIMATE, with INTIMATE for Integration of ice-core, marine and terrestrial records) and formally appointed it as WG of the SQS. This WG had to examine whether an exact definition of a Holocene subdivision would make sense and if so, how these boundaries (and thus the corresponding units) could be defined best. The discussion to introduce a Holocene lasted for several decades, but in 2012 the discussion paper by Walker et al. 2012, already mentioned here several times, was added. Mike Walker has been the head of this SQS working group. This 2012 paper was to be commented by the community worldwide, which took place, Yet, the formalisation process took until 14 July 2018 until ratification, requiring a formal proposal from the WG to the SQS. Upon that SQS voted, then the ICS, then the executive board of the IUGS. The voting procedure can also go back and forth several times if a revision is to be carried out, but it can also lead to rejection at any point. But the Holocene subdivisions are now formalised and should last. After a while the global community will certainly use the new names, because the advantages are obvious.

By the way, Walker et al. 2012 already mentioned the Anthropocene in their discussion paper, they write (quote):

The Anthropocene

It has been suggested that the effects of humans on the global environment, particularly since the Industrial Revolution, have resulted in marked changes to the Earth’s surface, and that these may be reflected in the recent stratigraphic record (Zalasiewicz et al., 2008). The term ‘Anthropocene’ (Crutzen, 2002) has been employed informally to denote the contemporary global environment that is dominated by human activity (Andersson et al., 2005; Crossland, 2005; Zalasiewicz et al., 2010), and discussions are presently ongoing to determine whether the stratigraphic signature of the Anthropocene is sufficiently clearly defined as to warrant its formal definition as a new period of geological time (Zalasiewicz et al., 2011a,b). This is currently being considered by a separate Working Group of the SQS led by Dr Jan Zalasiewicz and, in order to avoid any possible conflict, the INTIMATE/SQS Working Group on the Holocene is of the view that this matter should not come under its present remit. Nevertheless, we do acknowledge that although there is a clear distinction between these two initiatives, the Holocene subdivision being based on natural climatic/environmental events whereas the concept of the Anthropocene centres on human impact on the environ- ment, there may indeed be areas of overlap, for example in terms of potential human impact on atmospheric trace gas concentrations not only during the industrial era, but also perhaps during the Middle and Early Holocene (Ruddiman, 2003, 2005; Ruddiman et al., 2011). However, it is the opinion of the present Working Group that the possible definition of the Anthropocene would benefit from the prior establishment of a formal framework for the natural environmental context of the Holocene upon which these, and also other human impacts, may have been superimposed. (end of quote).

So how’s the geological anthropocene definition going? Again there was an initiative of an external group (emerged from several meetings at the Royal Society London). Since 2008, this group has existed in an extended form as the Working Group on the “Anthropocene” (AWS) set up by SQS. Again, the task is a) to test whether it makes sense to define an Anthropocene, and b) if so, where its lower boundary should be drawn and c) how this can be formally defined. These works are tedious, we wrote several conceptual papers and came to the conclusion that a start if the Anthropocene in the mid20th century would make the most sense (see many contributions in this block). We also discussed whether – in the sense of rapid formalisation – the definition would make sense by obky using a certain datum (the so-called GSSA process, Global Standard Stratigraphic Age). We suggested the date of the first atomic bomb experiment at Alamo Gordo (July 16, 1945) for discussion (Zalasiewicz et al. 2015). The discussion outside and within SQS however showed that a “classic” GSSP definition (via a Global Stratigraphic Section and Point, a so-called “Golden Spike”) would be better suited in order to achieve larger acceptance. Since then, we have compiled geosignal criteria for lower boundary detection (see e.g. Zalasiewicz et al. 2016, Waters et al. 2016, Zalasiewicz et al. 2017) and recently presented a comprehensive review on the possibilities of worldwide synchronous definition by using a GSSP and further “auxiliary sections” for further discussion (Waters et al. 2018). We have also made several references to the Walker et al. 2012 work and continue to see, and hence are in agreement with the Walker-WG, that the Holocene and the Anthropocene are very different on one hand, but also complementary on the other. We are currently investigating further candidates for possible Golden Spikes in cooperation with colleagues worldwide (not only within the AWG) and will need several additional meetings and further studies. A comprehensive status report is in print in book form (Zalasiewicz et al. 2018). We hope that we will be able to publish a final discussion paper in a few years’ time, followed by a formal proposal to SQS/ICS/IUGS, which will then be formally dealt with, just as described above for the Holocene. So it will still take some years until the Anthropocene appears formally in the Stratigraphic Chart, or not. However the fact that the Anthropocene assessment has already had a great scientific and social impact, even without a formal definition, is something I try to show time and again in this blog. Thus, we are currently living formally in the Quaternary, more precisely in the Holocene, even more precisely in the Meghalayan, but informally, given the human-made interventions on the Earth system and the resulting changes in the processes of geochemical cycling, weathering, transport and sedimentation, but also the our major imprint on the biosphere, as well as the resulting changes in sediment characteristics, it should be clear that from such a perspective we are already living in a different time, the anthropocene. Those who manage to erase entire mountain tops, crosscut new deep valleys, empty lakes run out or create new ones, dominate the pattern of organisms, change the climate and even let the sea level rise will not be surprised that this also has a long lasting geological-stratigraphic effect.

Literature:

a) the above frequently cited paper by Walker et al. (2012):

M. J. C. Walker M. Berkelhammer S. Björck L. C. Cwynar D. A. Fisher A. J. Long J. J. Lowe R. M. Newnham S. O. Rasmussen H. Weiss (2012): Formal subdivision of the Holocene Series/Epoch: a Discussion Paper by a Working Group of INTIMATE (Integration of ice‐core, marine and terrestrial records) and the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (International Commission on Stratigraphy).- Journal of Quaternary Science, 27 (7), 649-659. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2565

b) other literature cited in the blogpost as well as additonal recent publications of the Working Group on the “Anthropocene” (incomplete in backwards chronological order):

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C., Williams, M. & Summerhayes, C. (eds) (2018, in press): The Anthropocene as a geological time unit: an analysis, Cambridge University Press. Mit Beiträgen von Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Waters, Mark Williams, Colin Summerhayes, Martin Head, Reinhold Leinfelder, Jacques Grinevald, John McNeill, Naomi Oreskes, Will Steffen, Scott Wing, Phil Gibbard, Davor Vidas, Trevor Hancock, Anthony Barnosky, Bob Hazen, Andy Smith, Neil Rose, Agnieszka Gałuszka, An Zhisheng, Simon Price, Daniel deB. Richter, Sharon A Billings, James Syvitski, Ian Wilkinson, David Aldridge, Valentin Bault, Peter Haff, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Ian Fairchild, Michael Wagreich, Irka Hajdas, Catherine Jeandel, Alejandro Cearreta, Eric Odada, Erich Draganits, Matt Edgeworth, J. R. McNeill (> Info)

Colin N. Waters, Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Summerhayes, Ian J. Fairchild, Neil L. Rose, Neil J. Loader, William Shotyk, Alejandro Cearreta, Martin J. Head, James P.M. Syvitski, Mark Williams, Anthony D. Barnosky, An Zhisheng, Reinhold Leinfelder, Catherine Jeandel, Agnieszka Galuszka, Juliana A. Ivar do Sul, Felix Gradstein, Will Steffen, John R. McNeill, Scott Wing, Clement Poirier, Matt Edgeworth (2018): Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the Anthropocene Series: Where and how to look for potential candidates. . Earth Science Reviews, 178, 379-429, DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.12.016 (online first: accepted ms version, EARTH 2557: Dec. 30, 2017; final version: Mrch 2, 2018)

Colin N. Waters, Michael Wagreich, Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Summerhayes, Ian J. Fairchild, Neil L. Rose, Neil J. Loader, William Shotyk, Alejandro Cearreta, Martin J. Head, James P.M. Syvitski, Mark Williams, Michael Wagreich, Anthony D. Barnosky, An Zhisheng, Reinhold Leinfelder, Catherine Jeandel, Agnieszka Galuszka, Juliana A. Ivar do Sul, Felix Gradstein, Will Steffen, John R. McNeill, Scott Wing, Clement Poirier, Matt Edgeworth (2018):Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the Anthropocene Series: Where and how to look for potential candidates. Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 20, EGU2018-4590, 2018, European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2018, SSP2.1, online-Version

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters, Colin P. Summerhayes, Alexander P. Wolfe, Anthony D. Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Paul Crutzen, Erle Ellis, Ian J. Fairchild, Agnieszka Galuszka, Peter Haff, Irka Hajdas, Martin J. Head, Juliana A. Assunção Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, John R. McNeill, Cath Neal, Eric Odada, Naomi Oreskes, Will Steffen, James Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams (2017): The Working Group on the Anthropocene: Summary of evidence and interim recommendations.- Anthropocene doi:10.1016/j.ancene.2017.09.001

Zalasiewicz, J, Waters, CN, Wolfe, A P, Barnosky, AD, Cearreta, A, Edgeworth, M, Ellis, E, Fairchild,IJ, , Gradstein, FM, Grinevald, J, Haff, P, Head, MJ, Ivar do Sul, J, Jeandel, C, Leinfelder, R, McNeill, JR,Oreskes, N, Poirier, C, Revkin, A, Richter, DB, Steffen, W, Summerhayes, C, Syvitski, JPM, Vidas, D, Wagreich, M, Wing, S & Williams, M(2017), Making the case for a formal Anthropocene Epoch: an analysis of ongoing critiques, Newsletters on Stratigraphy, 50(2), 205-226, Online First DOI: 10.1127/nos/2017/0385 22 Mrch 2017,

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters & Martin Head (on behalf of all members of the Anthropocene Working Group) (2017): Correspondence: Anthropocene: its stratigraphic basis.- Nature, 541, p. 289, doi: 10.1038/541289b

Jan Zalasiewicz, Will Steffen, Reinhold Leinfelder, Mark Williams & Colin M. Waters (2016): Petrifying earth processes.- In: Clark, Nigel (ed), Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(3-2), #-# (Sage Journals), online first (13 March 2017): DOI: 10.1177/0263276417690587, printed vers. May 2017

Jan Zalasiewicz, Mark Williams, Colin N Waters, Anthony D Barnosky, John Palmesino, Ann-Sofi Rönnskog, Matt Edgeworth, Cath Neal, Alejandro Cearreta, Erle C Ellis, Jacques Grinevald, Peter Haff, Juliana A Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, John R McNeill, Eric Odada, Naomi Oreskes,Simon James Price, Andrew Revkin, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, Davor Vidas, Scott Wing, Alexander P Wolfe (2017): Scale and diversity of the physical technosphere: A geological perspective.- The Anthropocene Review, 4 (1), 9-22 doi:10.1177/2053019616677743 (online first publ.date Nov. 28, 2016)

Waters, C.N., Zalasiewicz, J., Barnosky, A.D., Cearreta, A., Edgeworth, M., Fairchild, I.J., Galuszka, A., Ivar do Sul, J.A., Jeandel, C., Leinfelder, R., Odada, E., Oreskes, N., Price, S.J., Richter, D.deB., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J.P., Wagreich, M., Williams, M., Wing, S., Wolfe, A.P. & An Zhisheng (2016): Assessing Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) candidates for the Anthropocene.- Paper # 2914, Abstract 35th International Geological Congress, Cape Town, South Africa 27th August – 4th September 2016. see here

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C.N., An, Z., Barnosky, A.D., Cearreta, A., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E.C., Fairchild, I.J.., Gałuszka, A., Haff, P.K., Ivar do Sul, J.A., Jeandel, C., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J.R., Odada, E.., Oreskes, N., Price, S.J., Richter, D. deB., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J.P., Wagreich, M., Williams, M., Wing, S. & Wolfe, A.P (2016): The Anthropocene: overview of stratigraphical assessment to date.- Paper # 3966, Abstract 35th International Geological Congress, Cape Town, South Africa 27th August – 4th September 2016. see here

Steffen, W., Leinfelder, R., Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Williams, M., Summerhayes, C., Barnosky, A. D., Cearreta, A., Crutzen, P., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E. C., Fairchild, I. J., Galuszka, A., Grinevald, J., Haywood, A., Sul, J. I. d., Jeandel, C., McNeill, J.R., Odada, E., Oreskes, N., Revkin, A., Richter, D. d. B., Syvitski, J., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Wing, S. L., Wolfe, A. P. and Schellnhuber, H.J. (2016): Stratigraphic and Earth System Approaches to Defining the Anthropocene.- Earth’s Future, 4 (8), 324-345, DOI:10.1002/2016EF000379 (publ. Jul 20, 2016)

Williams, M., Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Edgeworth, M., Bennett, C., Barnosky, A. D., Ellis, E. C., Ellis, M. A., Cearreta, A., Haff, P. K., Ivar do Sul, J. A., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J. R., Odada, E., Oreskes, N., Revkin, A., Richter, D. d., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J. P., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Wing, S. L., Wolfe, A. P. and Zhisheng, A. (2016): The Anthropocene: a conspicuous stratigraphical signal of anthropogenic changes in production and consumption across the biosphere.- Earth’s Future, 4, 34-53 (Wiley) doi: 10.1002/2015EF000339

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Patricia L. Corcoran, Anthony D. Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Agnieszka Galuszka, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, J.R. McNeill, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams, Alexander P. Wolfe & Yasmin Yonan (2016): The geological cycle of plastics and their use as a stratigraphic indicator of the Anthropocene.- Anthropocene, 13, 4–17, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2016.01.002 (Elsevier)

Colin N. Waters,Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin Summerhayes, Anthony D. Barnosky, Clément Poirier, Agnieszka Galuszka, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Erle C. Ellis, Michael Ellis, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, J. R. McNeill, Daniel de B. Richter, Will Steffen, James Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams, An Zhisheng, Jacques Grinevald, Eric Odada, Naomi Oreskes, Alexander P. Wolfe (2016): The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene.- Science 8 January 2016: Vol. 351 no. 6269 DOI: 10.1126/science.aad2622

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N Waters, Anthony D Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Erle C Ellis, Agnieszka Galuszka, Philip L Gibbard, Jacques Grinevald, Irka Hajdas, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, JR McNeill, Clément Poirier, Andrew Revkin, Daniel deB Richter, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, James PM Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams and Alexander P Wolfe (2015): Colonization of the Americas, “Little Ice Age” climate, and bomb- produced carbon: Their role in defining the Anthropocene – The Anthropocene Review August 2015 2: 117-127, doi:10.1177/2053019615587056

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N Waters, Anthony D Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Erle C Ellis, Agnieszka Galuszka, Philip L Gibbard, Jacques Grinevald, Irka Hajdas, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, JR McNeill, Clément Poirier, Andrew Revkin, Daniel deB Richter, Will Steffen, Colin Summerhayes, James PM Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams & Alexander P Wolfe (2015): Corresponcence: Epochs: Disputed start dates for the Anthropocene.- Nature, 520, p. 436, doi:10.1038/520436b

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C.N., Williams, M., Barnosky, A.D., Cerreata, A., Crutzen, P., Ellis, E., Ellis, M.E., Fairchild, I.J., Grinevald, J., Haff, P.K., Hajdas, I., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J., Odada, E.O., Poirier, C., Richter, D., Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., Syvitski, J.P.M., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Wing, S.L., Wolfe, A.P., An, Z. & Oreskes, N. Published online. When did the Anthropocene begin? A mid-twentieth century boundary is stratigraphically optimal. Quaternary International,, 383 (2015), 196-203.

Online first 12.1.2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2014.11.045

c) for additional papers by the author (also on the Anthropocene) see entrance page of reinhold-leinfelder.de

copyright: Reinhold Leinfelder, July 2018

This translation can be also accessed directly via https://tinyurl.com/meghalayan-commentary-RL

Original blogpost article in German: https://scilogs.spektrum.de/der-anthropozaeniker/meghalayan-oder-anthropozaen/

(for the original automatized google-translation see here (not recommended; since specific expressions are not translated correctly)

@Webbär,

es ist aber der Sprecher, der eine sinn-volle oder sinn-lose Aussge macht – es ist nicht die Aussage, die die Sinn macht.

@Reinhold Leinfelder,

da jegliche Acker- und Weidewirtschaft gestaltend in die Umwelt eingreift, indem sie z.B. auf den bewirtschafteten Flächen das Wachstum von Urwäldern verhindert, ist doch im Grunde das Holozän als durchgehend von menschlicher Aktivität geprägtes Interglazial mit dem Antropozän identisch – wofür braucht es einen neuen Namen? Nur für den kleinen Zeitabschnitt mit Plastiktüten und Getränkedosen im Sediment? Die sind doch in den Ländern, wo sie erfunden wurden, schon wieder am Aussterben – das Müllkippen-Zeitalter weicht dem Recycling-Zeitalter. Braucht es, sobald sich Mülltrennung und Recycling weltweit durchsetzt, dann nach dem Antropozän das Technozän…?

Darum geht es in diesem Beitrag eher weniger. Sie finden aber viele andere Beiträge dazu in diesem Blog. In a nutshell: wie jeder andere Organismus war auch der Mensch schon immer ein biologischer Faktor (Nahrungsaufnahme und Ausscheidung ist auch umweltrelevant). Seit dem Neolithikum/Holozän natürlich zunehmend, auch lokal/regional mit größeren Auswirkungen. Zum erdsystemaren/geologischen Faktor, der sich auf also gut wie alle Erdsystemsphären auswirkt, wird er aber erst durch die zunehmende Industrialisierung. Etwa ab dem großen Beschleunigungsschub nach dem 2.Weltkrieg können wir sagen, dass das Erdsystem nicht mehr dem holozänen entspricht, gleichzeitig ist dies anhand von Geosignalen synchron und weltweit nachweisbar. Ansonsten zur Technosphäre: das Ausmaß ist gigantisch. 0,01% der Biomasse (= Menschheit) hat nicht nur die Biosphäre komplett umgekrempelt (96% der Säugetierbiomasse besteht aus dem Menschen und seinen Säugernutztieren) sowie über 3/4 der eisfreien Kontnente hinsichtlich der holozänen Urnatur umgewandelt (bei den Meeren analog), sondern eben auch 30 Billionen Tonnen Materialien produziert. Im Vergleich: Menschheit wiegt so gut 300 Millionen Tonnen, das ist das 100.000 fache an Technomaterialien. Anders ausgedrückt: auf jeden lebenden Menschen kommen 4000 Tonnen Technomaterialien. Oder auch: jeder Mensch (der im Schnitt unter Berücksichtigung der Kinder ca 50 Kg wiegt) hat statistisch auf Land und Wasser verteilt etwa 7 Fußballfelder Platz (48456 m2). Auf jedem Quadratmeter der Welt liegen aber im Schnitt nochmals 50 Kg Technosphäre. Das ist beileibe kein Gefizzel, was bald wieder weg ist. Und wir benötigen all die (bislang dominant fossile) Energie, um die Rohstoffe dafür zu gewinnen, die Technomaterialien (Häuser, Straßen, Fahrzeuge, Maschinen, Kunststoffe etc) zusammenzubauen und auch zu betreiben. Kategorisch andere Zeiten als im Holozän. Wir verfrachten 10-30 mal mehr Sedimente als natürlichen Prozessen entsprechend, definieren wo Flüsse verlaufen, machen neue Seen, bestimmen wo sedimente abgelagert werden und wo nicht, verändern die lebewelt enorm, verändern das Klima und heben den Meeresspiegel.

Zum Vergleich mit anderen erdgeschichtlichen Zeiten siehe ggf auch hier: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2016EF000379