What impedes science communication? Results of an Extensive Survey with Young Researchers

BLOG: Heidelberg Laureate Forum

Carsten Könneker, Philipp Niemann, Christoph Böhmert

The demand for science communication to the public (the so-called external science communication) is currently becoming louder and louder against the background of the debates on “fake science” and populism. But by no means are all scientists responding to the call for science communication. So what impedes this sort of engagement? What do top young researchers – also considered the “next generation of professors” – see as obstacles to science communication? And how strongly do they agree with common prejudices such as that science communication is only something for the showmen among scientists or that it makes science itself more shallow?

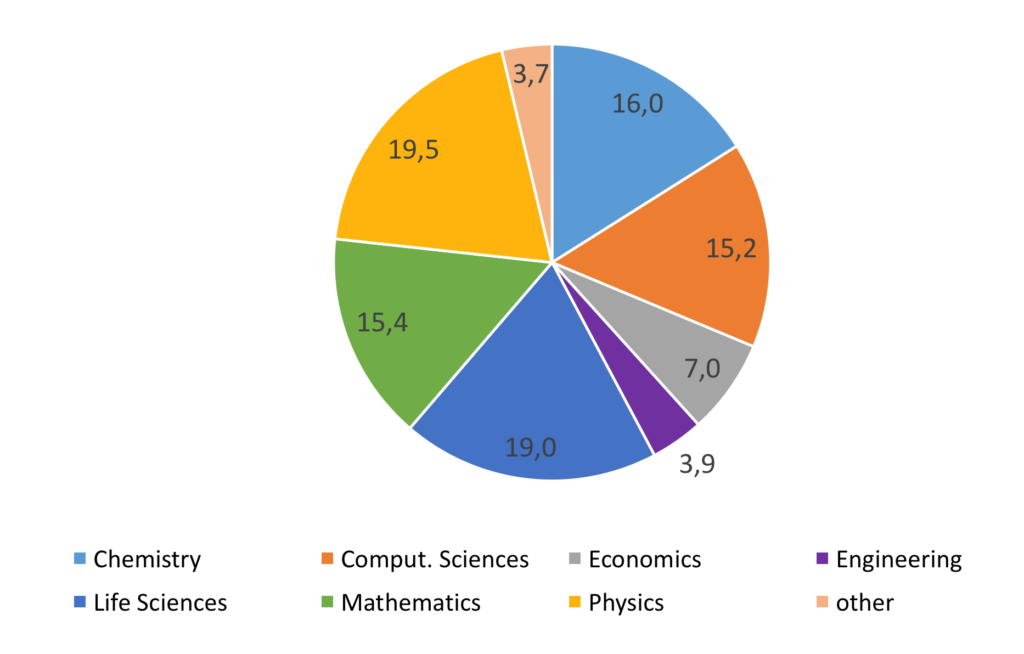

From 2014 to 2018, we surveyed the participants of the Heidelberg Laureate Forum and the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings. After quality control, we were left with 988 complete datasets of young scientists. These scientists carried out their research in 89 countries and none were older than 35 years of age. 41.5% of the interviewees were women, while 57.5% were men. Fig. 1 shows the distribution by discipline.

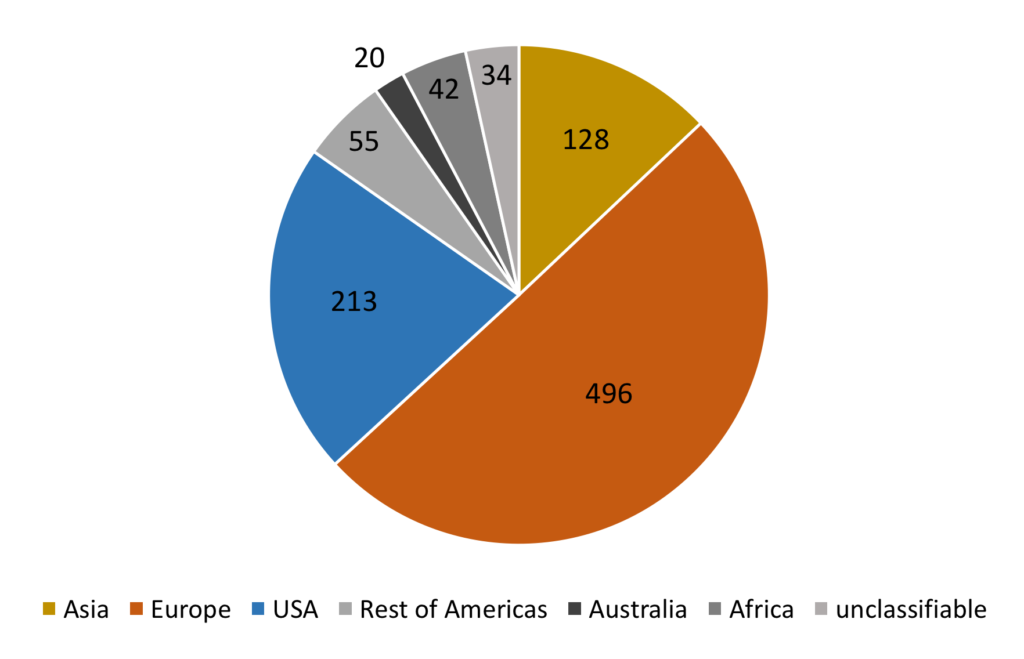

In the two years preceding the survey, most had conducted their research in Asia, Europe, and the USA (Fig. 2). In the analyses, stratified by continent, we have essentially limited ourselves to these three well-represented groups.

In another blog post we analyzed the commitment to and the attitudes towards science communication to the public. As far as their personal commitment to science communication is concerned, we found that differences between continents and scientific cultures are greater than those between disciplines – always provided that the selection process of young researchers for the major events we investigated was based on the same criteria in all countries.

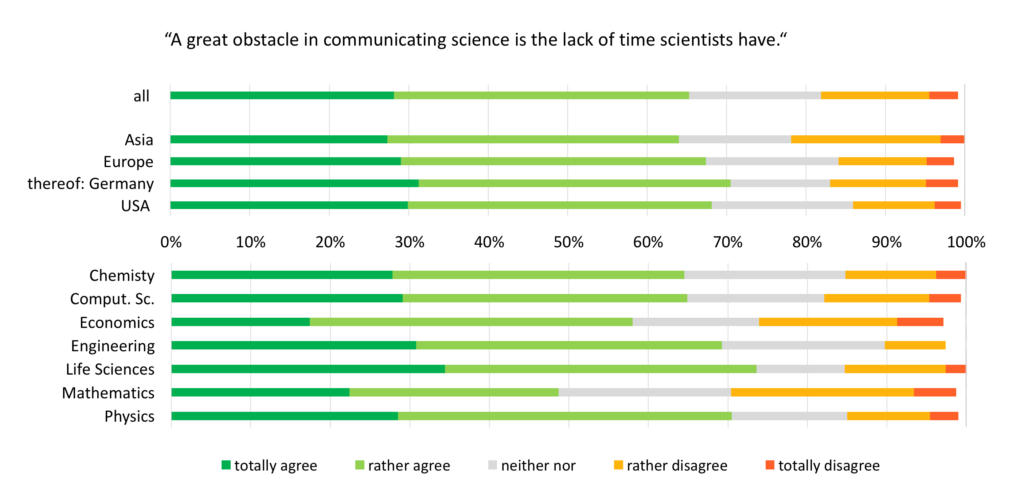

Apparently, whether a scientist works in Asia or in Europe makes a difference in how they speak about science with the public and what they think about science communication. Whether they are e.g. biologists or physicists did not matter as much. However, we also asked the participants if they agreed or disagreed with statements such as that “lack of time on the part of scientists is a great obstacle in communicating science.” Of three possible obstacles, the lack of time factor was clearly considered the most important. 65.2% of the young researchers surveyed totally or partially agreed with the corresponding statement, whereas only 17.2% partially disagreed or totally disagreed (Fig. 3). While the amount of those who agreed to this statement did not significantly differ between young researchers working on different continents, differences between researchers in different disciplines could be observed. Compared to researchers in other disciplines, mathematicians and economists see time pressure as less of an obstacle for science communication (however, more than half of them still agree that time trouble is an obstacle). In particular, the life scientists surveyed see the lack of time as an obstacle for science communication.

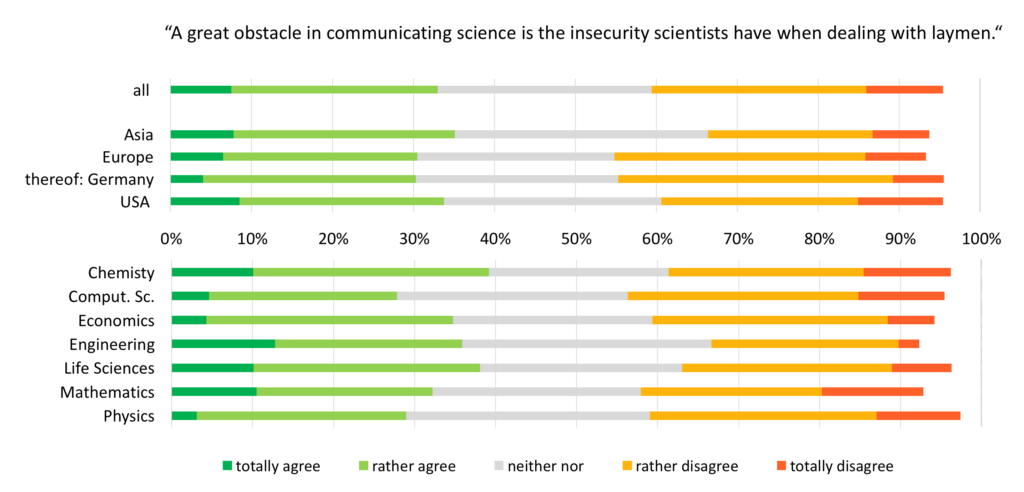

There was no clear consensus among the young researchers whether or not “the insecurity scientists have when dealing with laypersons is a great obstacle in communicating science.” 33.0% agreed, while 36.0% disagreed (Fig. 4). Researchers from Asia particularly see this insecurity as a problem. However, in this question, the differences between disciplines are also somewhat more prominent. Chemists, life scientists and engineers saw more of a problem here than physicists and computer scientists.

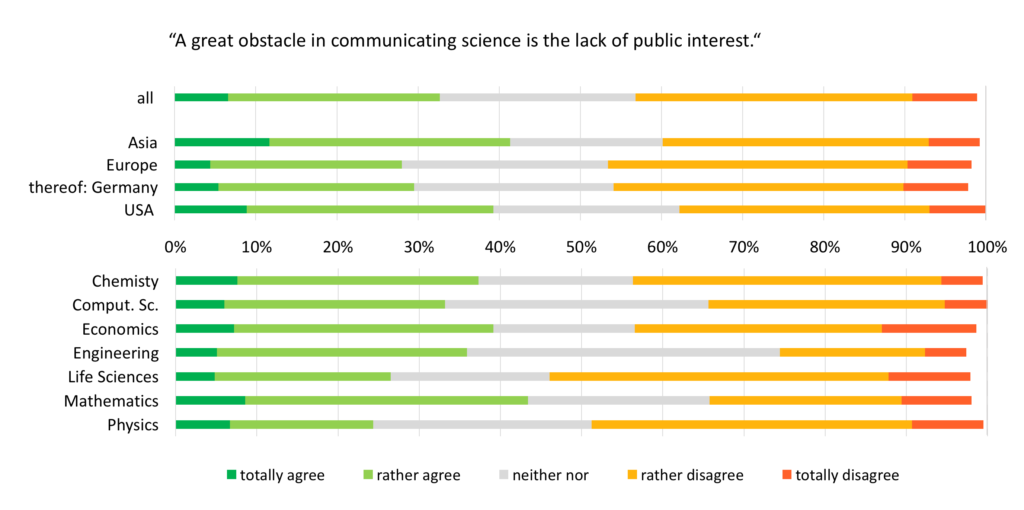

As another possible obstacle for science communication, we asked about a possible lack of public interest. Across the entire board, this statement was more strongly disagreed upon than agreed upon (42.1% to 32.7%; see Fig. 5). However, the answers differ considerably with subgroups. Young researchers from Asia and the USA saw greater disinterest in science among the public than their colleagues from Europe. And mathematicians, economists and chemists agreed much more with this statement than physicists and life scientists.

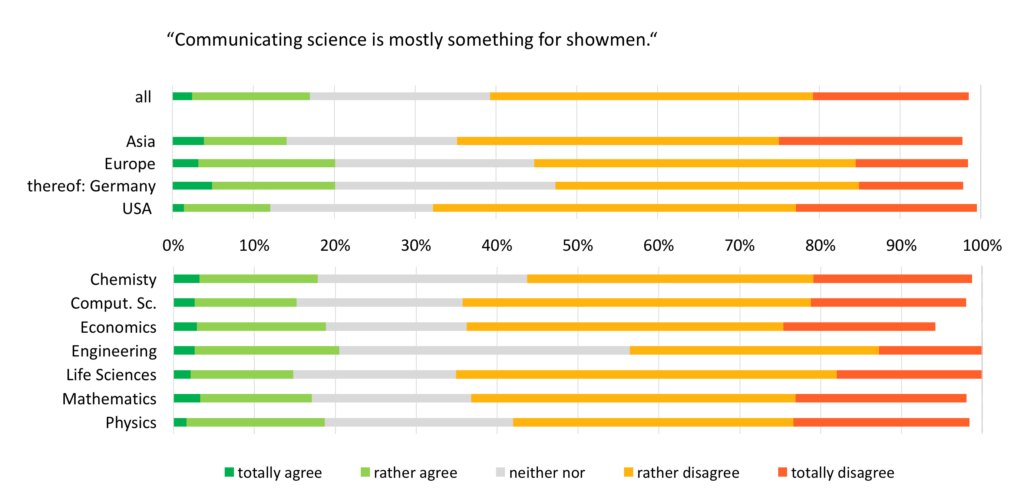

Some believe that a major obstacle in effectively conveying science is that scientists believe that “communicating science is mostly something for showmen.” We wanted to know whether the young researchers in our survey agree with that prejudice. The answer is: mostly not. Only 17.0% of the young researchers agreed, whereas a large majority, 59.2%, disagreed with it (Fig. 6). With 77.3%, researchers in the USA disagreed the most with this statement. When comparing the response behavior by disciplines, it is noticeable that the least resistance to the statement comes from scientists in the field of engineering.

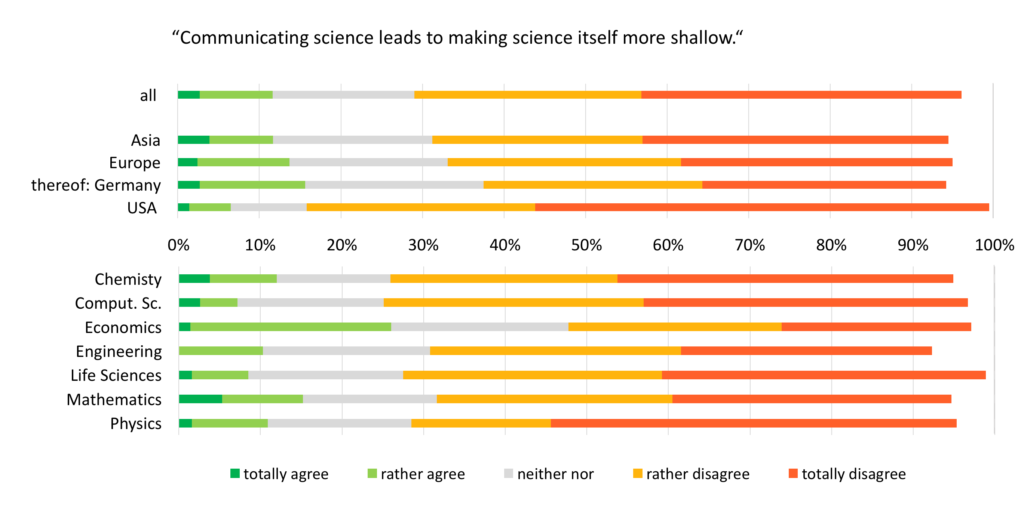

Do public outreach and societal dialogue have a negative effect on science itself? Finally, we confronted the young researchers with the statement “communicating science leads to making science itself shallower.” A total of 67.0% completely or partially disagreed with this statement. They were opposed by only 11.6% who totally or partially shared this view (Fig. 7). 83.6% of young researchers who conducted their research in the USA disagreed with this statement, which is particularly high. Subdivided by discipline, economists agreed the most with 26.0%, who clearly stand out from their colleagues in all other disciplines. While one can assume that the scientific culture in the USA simply encompasses communicating science and thus induces the particular response behavior of researchers in the USA, reasons for the differing response behavior of the economists are difficult to discern.

In brief: When asked about obstacles to and typical prejudices against science communication, a lack of time can be identified as the strongest factor. Uncertainty in dealing with laypersons and a lack of interest on the other hand are far behind, although there are interesting disciplinary differences when looking at it in detail. In addition, our data suggest that prejudices against science communicators and lay audiences are rather less present in young researchers in the USA compared to their colleagues in Europe and Asia.

Carsten Könneker is editor-in-chief of “Spektrum der Wissenschaft”, the German edition of “Scientific American”. From 2012 to 2018, he headed the Chair of Science Communication and Science Studies at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. He also is the founding director (2012-2015) of the National Institute for Science Communication (NaWik) in Karlsruhe.

Philipp Niemann is the scientific head of the National Institute for Science Communication (NaWik).

Christoph Böhmert recently completed his PhD at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.