Tür 9: Delphin und Füllen

Zwei sehr kleine Sternbilder des Sommerhimmels sind der Delphin und das Pferdchen (Füllen). Das Füllen taucht erst bei Ptolemaios als Sternbild auf, wenngleich die Sterne gewiss schon früher verzeichnet waren – nur entweder frei oder dem Delphin oder dem Pegasus zugeschrieben. Hipparch (-2.Jh.) nennt kein solches Sternbild und Aratos auch nicht, aber bei Eratosthenes (-3.Jh.) wird es genannt, ohne als eigenständig beschrieben zu werden. Das Konzept, dem großen Pferd ein Junges beizugeben, könnte also deutlich älter sein als der Almagest – es sei denn, dieser Text wird Eratosthenes nur versehentlich zugeschrieben und ist tatsächlich von einer späteren Hand eingefügt: Man kann das nie so genau wissen, denn Eratosthenes’ Buch ist, wie gesagt, nicht überliefert: es hat nur irgendwer in der Spätantike, dem das Buch noch vorlag, dieses genutzt, um das Lehrgedicht von Arat zu kommentieren und dann haben sich in den letzten Dekaden fleißige Philologe dran gemacht, diese Textschnipsel zu sammeln und zu übersetzen, um den alten Text zu rekonstruieren. Es kann also sein, dass die Zuschreibung an Eratosthenes hier ein Irrtum ist – wissen wir nicht.

Das Füllen ist jedenfalls auch eines jener kleinen Sternbilder, die auf dem Atlas Farnese fehlen.

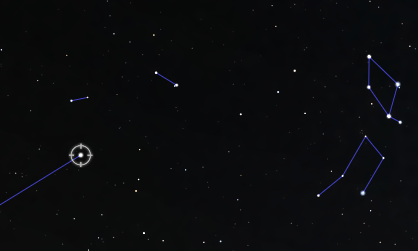

Der Delphin ist allerdings abgebildet – und zwar so groß, dass er die Sterne des späteren Füllen auf der Schwanzflosse hat. Der moderne Betrachter wird die Figur mit dem breiten Entenschnabel vllt. erst beim zweiten Hinschauen als Meeressäuger erkennen:

Door 9: Dolphin and Bust of a Horse

Two very small constellations of the summer sky are the Dolphin and the Little Horse. The Filling appears as a constellation only in Ptolemy, although the stars were certainly listed earlier – only either free or attributed to the Dolphin or Pegasus. Hipparchus (-2nd century) does not mention such a constellation and neither does Aratos, but in Eratosthenes (-3rd century) it is mentioned without being described as independent. The concept of adding a young to the great horse could therefore be considerably older than the Almagest – unless this text is only attributed to Eratosthenes by mistake and is actually inserted by a later hand: One can never be sure, because Eratosthenes’ book, as I said, has not survived: only someone in late antiquity, who still had the book, used it to comment on Arat’s doctrinal poem and then, in recent decades, diligent philologists have set about collecting and translating these text snippets in order to reconstruct the ancient text. So it may be that the attribution to Eratosthenes is a mistake here – we don’t know.

In any case, the Filling is also one of those small constellations that are missing from the Atlas Farnese.

The dolphin, however, is depicted – and so large that it has the stars of the later Füllen on its tail fin. The modern viewer may only recognise the figure with the broad duck’s beak as a marine mammal on second glance:

Babylon

Oft wird der Delphin als das Babylonische Sternbild “der Leichnam” interpretiert, das sich irgendwo in dieser Gegend befinden muss. Genaue Koordinaten haben wir nicht.

Wie ich in früheren Posts erläuterte, scheint es mir aber aus Gründen der Transformation nach Griechenland und Überführung ins Sternbild Adler-mit-Antinuos sinnvoller, den babylonischen Leichnam südlicher zu platzieren. Dann wäre in dieser Gegend des Delphins Platz für das babylonische Sternbild “Schwein”, das sich ebenfalls irgendwo hier befinden muss und dem andernfalls nur schwache Sternchen “irgendwo im nirgendwo” zugeschrieben werden könnten. Die kleine, aber auffällige Gruppe Delphinus zu einer Figur zu machen erscheint mir plausibler und daher passt der Vorschlag, den “Toten Mann” unter den Adler zu setzen auch zu diesem Sternbildchen.

Lustig ist dann erst recht, dass Joh. E. Bode statt “Delphin” lieber das germanische Wort “Meerschwein” wählt. Damit meint er nicht einen Hamster 😉 sondern einen Schweinswal, also die besonders kleinen Meeressäuger.

Babylon

The dolphin is often interpreted as the Babylonian constellation “the corpse”, which must be somewhere in this area. We do not have exact coordinates.

However, as I explained in earlier posts, for reasons of transformation to Greece and transfer to the constellation Eagle-with-Antinuos, it seems to me to make more sense to place the Babylonian corpse more to the south. Then there would be room in this area of the dolphin for the Babylonian constellation “Pig”, which must also be somewhere here and to which otherwise only faint little stars “somewhere in nowhere” could be attributed. Making the small but conspicuous group Delphinus into a figure seems more plausible to me and therefore the suggestion to place the “Dead Man” under the eagle also fits this constellation.

It is even funnier that Joh. E. Bode chooses the Germanic word “guinea pig” instead of “dolphin”. He does not mean a hamster 😉 but a porpoise, i.e. the particularly small marine mammals.

China

Im Fernen Osten war der Delphin als zwei Schalen gedacht worden. Wie bei Aschenputtel ist die eine Schale mit gutem, die anderen mit schlechtem gefüllt.

Unser Sternbild Füllen (Fohlen), also kleines Pferd oder eigentlich “Pferdebüste”, das erst bei Ptolemäus und irgendwie aus dem Nichts aufzutauchen scheint, ist bekanntlich überhaupt nicht anschaulich. Daher gibt es auch in China keine eigene Gruppe ab, sondern einige seiner Sternchen werden als Richter interpretiert, andere als “die Leere”, die bis zum Wassermann reicht.

China

In the Far East, the dolphin was thought of as two bowls. Like Cinderella, one bowl is filled with good, the other with bad.

Our constellation Filling (Foal), i.e. small horse or actually “horse bust”, which only seems to appear in Ptolemy and somehow out of nowhere, is not at all vivid, as is well known. This is why it does not form a group of its own in China, but some of its asterisks are interpreted as judges, others as “the void”, which reaches as far as Aquarius.