Tür 8: Pfeil und Adler

Der Pfeil ist ein kleines, leicht auffindbares, wenngleich nicht sehr auffälliges Sternbild im Sommerdreieck. Auf dem Atlas Farnese ist er nicht abgebildet, aber das will nichts heißen, denn die kleinen Sternbilder als Relief aus dem Stein zu hauen, mag schwierig gewesen sein. Bei Ptolemaios wird er im Almagest genannt und so beschrieben, wie wir ihn kennen und auch bei Hipparch wird der Aufgang des Pfeils (als zwölftes Sternbild) genannt. Die mathematische Astronomie von Hipparch und Ptolemaios ebenso wie die poetische bei Aratos hat dieses Sternbild also durch alle Jahrhunderte hinweg gekannt.

Adler

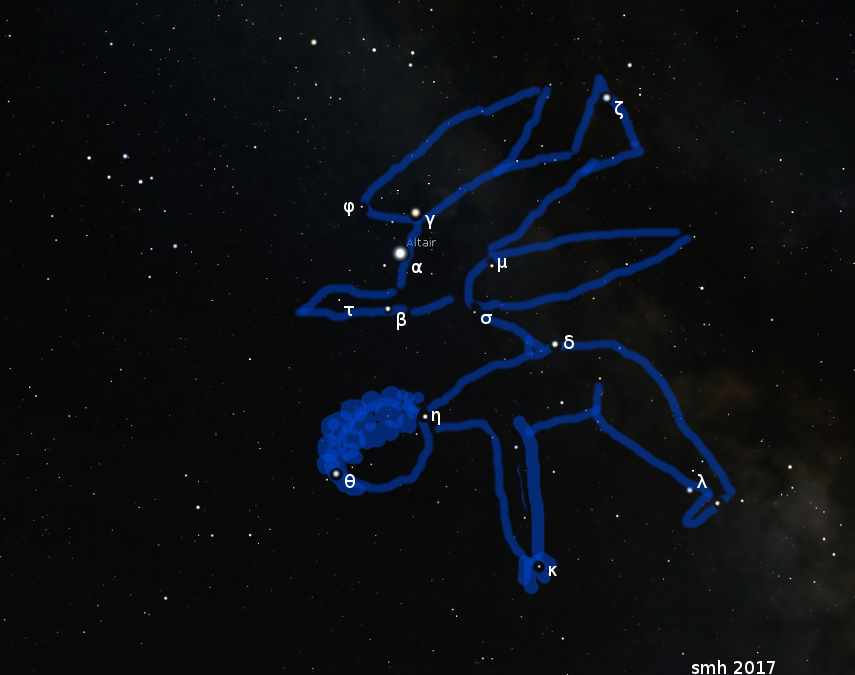

Der Adler ist durch seinen hellen Stern Atair ein wichtiger Bestandteil des Sommerdreiecks. Atair wird im Englischen mit einem “l” geschrieben, also Altair. Das liegt an verschiedenen Transliterationen aus dem Arabischen: Das “L” des arabischen Artikels wird zwar im Arabischen geschrieben, ist hier aber stumm und darum darf man es auch in phonetischer Schreibung weglassen; ich hatte darüber in einem früheren Post einmal berichtet.

Sternbildhistorisch ist die interessantere Frage nach der Orientierung des Vogels auf dem Globus: In modernen Planetarien ist er meist so gelegt, dass der Kopf auf dem hellsten Stern liegt; so fliegt er dem Schwan entgegen und rechtfertigt den arabischen Namen an-nasr at-tair, der aufsteigende Adler, des hellsten Sterns. Auf dem Atlas Farnese hängt er aber kopfüber, so dass ihm der Schwan quasi in die Füße pickt:

Door 8: Arrow and Eagle

The Arrow is a small, easy to find, although not very conspicuous constellation in the Summer Triangle. It is not depicted on the Atlas Farnese, but that does not mean anything, because it may have been difficult to carve the small constellations out of the stone in relief. In Ptolemy’s Almagest it is mentioned and described as we know it, and Hipparchus also mentions the rising of the arrow (as the twelfth constellation). The mathematical astronomy of Hipparchus and Ptolemy as well as the poetic astronomy of Aratus have known this constellation throughout the centuries.

Eagle

The eagle is an important part of the summer triangle due to its bright star Atair. Atair is written in English with one “l”, i.e. Altair. This is due to different transliterations from Arabic: The “L” of the Arabic article is written in Arabic but is silent here and that is why you may omit it even in phonetic spelling; I had reported on this once in an earlier post.

Constellation-historically, the more interesting question is the orientation of the bird on the globe: in modern planetariums it is usually placed so that the head is on the brightest star; thus it flies towards the swan and justifies the Arabic name an-nasr at-tair, the soaring eagle, of the brightest star. On the Atlas Farnese, however, he hangs upside down, so that the swan virtually pecks him in the feet:

Im Almagest – und übrigens auch in Joh. Elert Bodes Sternkarten aus dem 18. Jahrhundert – fliegt der Adler von West nach Ost und hat Atair am Nacken; optional (z.B. im Almagest) kann er dabei auch einen Jüngling namens Antinous tragen. Antinous war ein männlicher Geliebter eines römischen Kaisers, den Neider ermordeten, weshalb er von seinem mächtigen Freund in Trauer an den Himmel versetzt worden war.

In the Almagest – and incidentally also in Joh. Elert Bode’s star charts from the 18th century – the eagle flies from west to east and has Atair on its neck; optionally (e.g. in the Almagest) it can also carry a youth named Antinous. Antinous was a male lover of a Roman emperor whom envious men murdered, so he was transferred to the sky in mourning by his powerful friend.

Babylon

Meine “steile These” ist, dass dies eine babylonische Vorlage hat, nämlich die babylonischen Sternbilder Adler (oder Aßfresse Geier) und “der Leichnam”, der sich irgendwo in dieser Himmelsgegend befinden muss.

Ich hatte im Sommer mehr dazu geschrieben.

Darum sei hier noch Joh. Elert Bodes Variante der römischen Dichter aus der Uranographia (1801) zitiert:

“Nach verschiedenen Dichtern der Vorzeit war dies der Adler, welcher den schönen Knaben Ganymed, einem Sohn des phrygischen Königs Tros, am Berge Ida für den Jupiter raubte. Antinuos war gleichfalls ein schöner Knabe aus Bithynien, den der Kayser Hadrian an seinem Hofe hatte; nach anderen ist hier gleichfalls Ganymedes verstirnt.(…)”

So kann man bei Bedarf auf die Namensgleichheit zum modernen Jupitermond Ganymed verweisen und ist bei haptischen Objekten des Sonnensystems angekommen.

Babylon

My “steep thesis” is that this has a Babylonian template, namely the Babylonian constellations of the eagle (or eater vulture) and “the corpse”, which must be somewhere in this region of the sky.

I wrote more about this in the summer (in German).

Therefore, Joh. Elert Bode’s variant of the Roman poets from the Uranographia (1801) should be quoted here:

“According to various poets of ancient times, this was the eagle that stole the beautiful boy Ganymede, a son of the Phrygian king Tros, on Mount Ida for Jupiter. Antinuos was also a beautiful boy from Bithynia, whom the Emperor Hadrian had at his court; according to others, Ganymedes also died here.(…)”.

Thus, if necessary, one can refer to the similarity in name to the modern moon of Jupiter, Ganymede, and has arrived at haptic objects of the solar system.

China

Im Chinesischen, das auch nach Japan und Korea kopiert wurde, ist der helle Stern Atair des Adlers eine Trommel am Fluss (der Milchstraße) und diese wird flankiert von der Rechten Flagge (Rest vom Adler) und der Linken Flagge (unser Pfeil).

China

In Chinese, which has also been copied to Japan and Korea, the bright star Atair of the eagle is a drum on the river (the Milky Way) and this is flanked by the Right Flag (rest of the eagle) and the Left Flag (our arrow).