Tür 10: Pferd und Andromeda

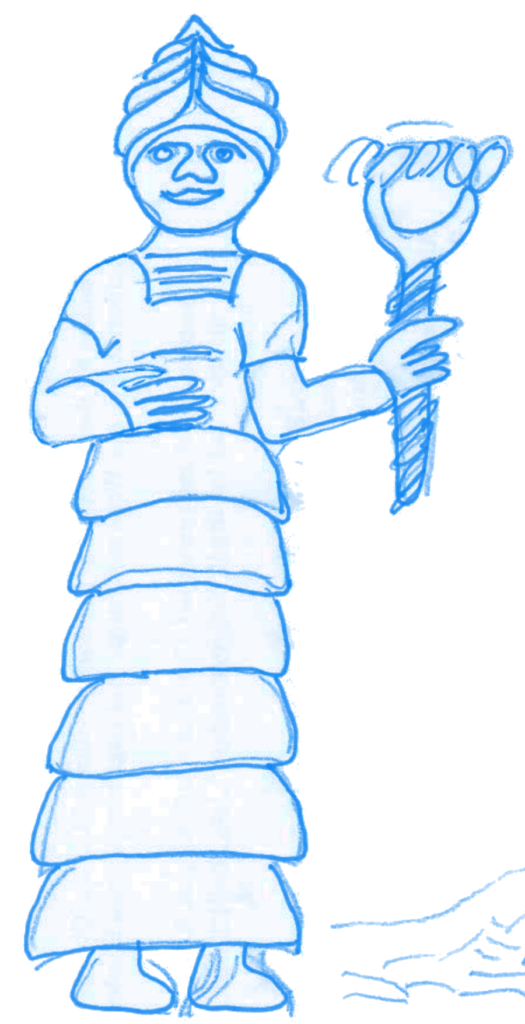

Andromeda, die schöne Tochter von Kassiopeia und Kepheus, ist auf dem Atlas Farnese mit einem langen, mehrstufigen Kleid dargestellt. Der Saum über ihren Füßen wird durch schwache Sterne markiert, die andere Stufe bildet die Sternkette über beta Andromedae bis zu M31, der Andromeda-Galaxie – die übrigens, obwohl deutlich mit freiem Auge erkennbar, in antiken Sternkatalogen nicht vorkommt.

Aratos beschreibt die Dame als leidend, angekettet, aber im Bild ist davon nichts erkennbar:

Door 10: Horse and Andromda

Andromeda, the beautiful daughter of Cassiopeia and Cepheus, is depicted on the Atlas Farnese with a long, multi-level dress. The hem above her feet is marked by faint stars, the other tier forms the chain of stars above beta Andromedae up to M31, the Andromeda galaxy – which, by the way, although clearly visible to the naked eye, does not appear in ancient star catalogues.

Aratos describes the lady as suffering, chained, but nothing of this is visible in the image:

Ihr Kopfstern überlappt antik übrigens konsequent, d.h. in allen erhaltenen Beschreibungen, mit dem Nabel des Pferdes. Der Stern hat folglich zwei antike Namen und daher auch zwei arabische Namen. Heute ist er eindeutig “alpha Andromedae”, also nicht im Sternbild Pegasus. Darum ist es – streng genommen – falsch von einem Pegasus-Viereck zu sprechen, sondern besser sagt man hier Herbstviereck.

Das Pferd – heute Pegasus

Pegasus ist übrigens auch ein moderner Name. Planetariumsmoderatoren amüsieren sich oft darüber, dass man das Ross nur mit viel Phantasie, aber sicher keine Flügel daran erkennen kann. Tja – das liegt daran, dass es antik auch keine Flügel hatte, sondern diese erst modern angedichtet bekam, als man es in Pegasos umtaufte. Dass es sich bei dem Rosse um das geflügelte Pferd handeln könne, schreibt auch Eratosthenes bereits auf – nur sagt er eben, dass das nicht sein könne, weil das halbe Ross keine Flügel hat. Die Astronomen der Neuzeit wussten es offenbar besser… 🙂

Das Pferd, wie es auf griechisch einfach hieß, ist halb von der Andromeda verdeckt, also nur bis zum Nabel am Himmel abgebildet. Auf dem Atlas Farnese haben wir in dieser Region zahlreiche Kuriositäten; insbesondere finden wir es auch begleitet von den zwei Fischen des Sternbildes Fische.

By the way, in antiquity her head star overlaps consistently, i.e. in all preserved descriptions, with the horse’s navel. Consequently, the star has two ancient names and therefore also two Arabic names. Today it is clearly “alpha Andromedae”, i.e. not in the constellation Pegasus. That is why it is – strictly speaking – wrong to speak of a Pegasus quadrangle, but it is better to say autumn quadrangle here.

The horse – today Pegasus

Pegasus, by the way, is also a modern name. Planetarium presenters are often amused by the fact that you can only recognise the steed with a lot of imagination, but certainly no wings on it. Well, that’s because it didn’t have wings in ancient times either, but was only given them in modern times when it was renamed Pegasos. Eratosthenes also wrote that the horse could be a winged horse, but he said that it could not be because half the horse had no wings. The astronomers of modern times obviously knew better… 🙂

The horse, as it was simply called in Greek, is half covered by Andromeda, i.e. it is only depicted in the sky up to its navel. On the Atlas Farnese we have numerous curiosities in this region; in particular we also find it accompanied by the two fishes of the constellation Pisces.

Babylon

Das Herbstviereck, das an unserem Himmel die beiden Sternbilder Andromeda und Pegasus (wie es laut IAU-Nomenklatur nun heißt) verbindet, ist übrigens babylonisch das Sternbild “Feld”. Ein “Feld” ist ein Flächenmaß, also als würden wir eines unserer Sternbild ein “Hektar” oder “Quadratmeter” nennen. Warum diese mathematische Einheit an den Himmel versetzt wurde, erschließt sich uns nicht, aber vermutlich hat es juristische Bedeutung.

Daneben, da, wo später die Prinzessin Andromeda angesiedelt wird, ist (allerdings um 90° gedreht gegenüber Andromeda) auch eine weibliche Figur: Die Göttin Anunitu, ein anderer Name für die Göttin der Liebe und des Krieges, Ischtar.

Die Babylonier hatten also schon recht gut verstanden: “Love is a battlefield”. 😉 Nein, Spaß beiseite: Sie hatten eine Göttin für die sexuelle Liebe, nicht aber für die romantische Liebe – Ischtar war daher auch eine Kriegsgöttin, wird mitunter auch mit Waffen dargestellt und nicht wie Aphrodite als naktes leichtes Mädchen.

Babylon

By the way, the autumn quadrangle that connects the two constellations Andromeda and Pegasus (as it is now called according to IAU nomenclature) in our sky is Babylonian for the constellation “field”. A “field” is a measure of area, so as if we were to call one of our constellations a “hectare” or “square metre”. Why this mathematical unit was placed in the sky is not clear to us, but presumably it has legal significance.

Next to it, where the princess Andromeda is later placed, there is also a female figure (though rotated 90° with respect to Andromeda): the goddess Anunitu, another name for the goddess of love and war, Ishtar.

So the Babylonians had already understood quite well: “Love is a battlefield” 😉 No, joking aside: they had a goddess for sexual love, but not for romantic love – Ishtar was therefore also a goddess of war, is sometimes depicted with weapons and not as a naked light girl like Aphrodite.

China

Die Gruppe der babylonischen Göttin Anunitu ist chinesisch das Sternbild “Beine”. Man weiß nicht genau, von wem, aber das spielt wohl keine Rolle. Pegasus zerfällt in die Sternbilder “Wand” und “Feldlager” (Zelt).

China

The group of the Babylonian goddess Anunitu is the constellation “legs” in Chinese. We don’t know exactly from whom, but it probably doesn’t matter. Pegasus breaks down into the constellations “wall” and “camp” (tent).