Die Dendera-Sternkarte in Stellarium

Die populäre Planetariumssoftware Stellarium wurde während meines Aufenthalts an der Bibliothek von Alexandria in der Version 1.0 released: Herzliche Gratulation den beiden Haupt-Developern Alexander Wolf und Georg Zotti, die nach über zehn Jahren(!) Arbeit nun diesen super-Erfolg feiern dürfen!!! Erfunden wurde Stellarium vor etwa zwanzig Jahren von dem damaligen Studenten Fabien Chéreau, der heute mit der kommerziellen Version von Stellarium seinen Unterhalt verdient. Für wissenschaftliche Exaktheit zeichnen allerdings die beiden oben genannten Astro-Programmierer verantwortlich, die an einer pädagogischen Hochschule bzw. als Programmierer am Institut für Virtuelle Archäologie arbeiten. Die Früchte ihrer Software-Entwicklung stellen sie der Welt kostenlos und quelloffen zur Verfügung.

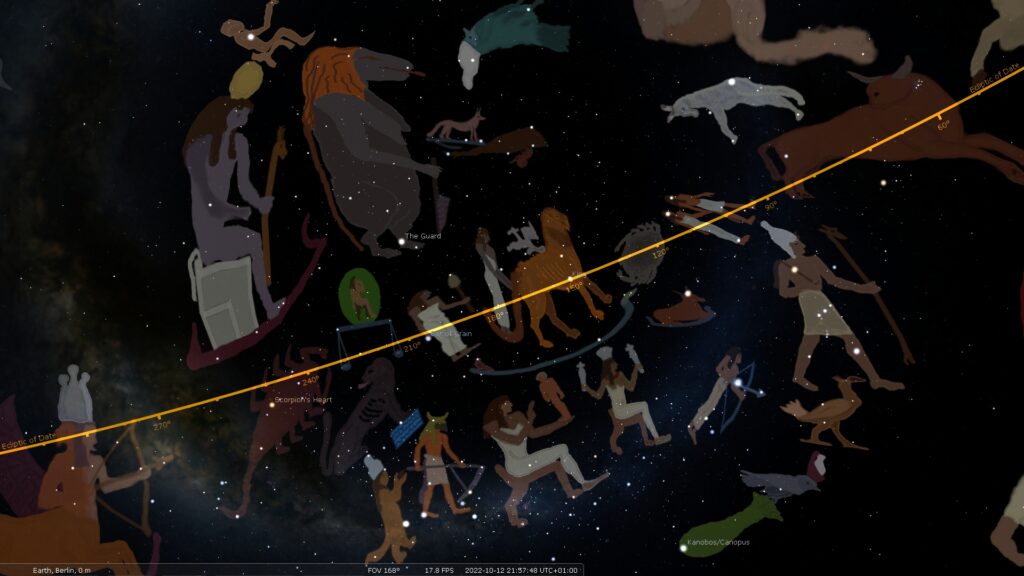

Stellarium zeichnet sich u.a. dadurch aus, dass alle Forschenden beitragen können und daher nicht nur die Software selbst, sondern auch die Datensätze, auf die sie zurückgreift, eine wahre Fundgrube sind. Nicht nur Satellitendaten, moderne Himmelsvermessungen und Bilder des Alls in allen Wellenlängen, sondern auch historische Himmelsdarstellungen sind in aller Korrektheit auf dem aktuellen Stand verfügbar. Die Sternkarte des so genannten “Tierkreises” von Dendera habe ich letztes Jahr eingearbeitet (hier die Quelldaten vom Louvre Paris). Wie bereits berichtet, ist das fragliche Relief nicht nur ein Zodiak, sondern wahrlich eine Art Planisphäre – also eine Art Grundplatte von eine “drehbare Sternkarte”.

The popular planetarium software Stellarium was released in version 1.0 during my stay at the Library of Alexandria: Congratulations to the two main developers Alexander Wolf and Georg Zotti, who can now celebrate this super success after more than ten years(!) of work!!! Stellarium was invented about twenty years ago by the then student Fabien Chéreau, who today earns his living with the commercial version of Stellarium. However, the two astro-programmers mentioned above, who work at a teacher training college and as programmers at the Institute for Virtual Archaeology respectively, are responsible for scientific accuracy. They make the fruits of their software development available to the world free of charge and open source.

One of Stellarium’s distinguishing features is that all researchers can contribute and therefore not only the software itself, but also the data sets it draws on are a veritable treasure trove. Not only satellite data, modern celestial surveys and images of space in all wavelengths, but also historical celestial representations are available in all their correctness at the current state. I included the star map of the so-called “zodiac” of Dendera last year (here is the source data from the Louvre Paris). As already reported, the relief in question is not only a zodiac, but truly a kind of planisphere – i.e. a kind of base plate of a “revolving star map”.

Der Dendera-Zodiak

Der Tierkreis ist hier einfach erklärt: Aries, der Widder, ist als Lämmchen dargestellt. Taurus, der Stier, als (ganzer) Stier, was interessant ist, weil der babylonische Stier vermutlich stets halb war (erstens sieht man es so am Himmel, zweitens wird der Himmelsstier – wie das Sternbild wörtlich heißt – im Gilgamesch-Epos vom Heroen und seinem Freund Enkidu geteilt und geopfert). Gemini, die Zwillinge, sind ägyptisch das Geschwister-Ehepaar aus Luftgott Schu und Luftfeuchtigkeitsgöttin Tefnut. Cancer, der Krebs, ist oft ein Skarabäus, Leo, der Löwe, ist ein Löwe. Die Jungfrau, die babylonisch ursprünglich nicht als Sternbild existierte, sondern als Sternbild Ackerfurche mit der Göttin Schala assoziiert worden war und erst im Uruk des 1. Millenniums als diese umgedeutet wurde, ist wie die Göttin Schala in Dendera dargestellt. Libra, die Waage, und Scorpius, der Skorpion, sind in der gewohnten Form dargestellt. Sagittarius trägt zwar eine ägyptische Doppelkrone, ist aber wie ein (ungewohnt janusköpfiger) babylonischer Gott Pabilsang dargestellt. Capricornus, der Ziegenfisch, ist unverändert als der gutartige babylonische Dämon wiedergegeben, Aquairus, der Wassermann, wird nicht in der babylonischen Form des Gottes der Weisheit, Zauberkraft und des Quells von Euphrat und Tigris wiedergegeben, sondern als der ägyptische Nil-Gott, was als direkte Übersetzung einer fremden in die eigene Kultur gelesen werden kann. Bemerkenswert ist das Bild der Fische, die mit einem V-förmigen Band verbunden abgebildet werden wie es Aratus beschreibt, jedoch in der babylonischen Uranographie nicht vorkommt. Bezeichnenderweise säumen diese verknüpften Fische ein Rechteck aus Wasser, das an der Stelle des babylonischen Sternbilds „Iku“ (ein Flächenmaß) liegt. Die Tierkreisfiguren lassen also alle mindestens babylonische Reminiszenzen erkennen, wenn sie nicht sogar direkte Übernahmen sind.

Neben den zwölf bekannten Figuren gibt es im Tierkreis ja auch – damals wie heute – die Sternbilder Orion (ägyptisch: Osiris), Ophiuchus (Schlangenträger), Cetus (Wal) und Sextant. Was historisch an der Stelle von Sextant war, wissen wir nicht – vllt. war sie einfach leer. An Stelle des griechischen Ophiuchus gibt es im Bild von Dendera eine große Gottheit auf einem Thron und an der Stelle von Cetus gibt es zwei weibliche Gottheiten mit Wadjet-Szepter. In beiden Fällen ist die Bedeutung dieser Figuren unklar und sicher nicht babylonisch. Vielleicht geben sie für Ägyptologen, die klüger sind als ich, irgendwann einmal einen Hinweis auf ältere ägyptische Sternbilder.

Neben der „nördlichen Konstellation“, deren zentrales Element die sieben Sterne des Großen Wagens bilden (ägyptisch: Stierschenkel), Orion-Osiris und dem Tierkreis, der ja ursprünglich (babylonisch, nachgewiesen in MUL.APIN) der „Pfad des Mondes“ war, der sich (astronomisch gesehen) nicht verändert hat, gibt es nur wenige Anhaltspunkte. Der Rest wird durch Interpolation aufgefüllt. Ausgehend von diesen Anker-Sternbildern, können wir also die Darstellung des „runden Tierkreises“ als eine Art Planisphäre verstehen, mit deren Hilfe möglicherweise auch weitere (ältere?) ägyptische Sternbilder erschlossen werden könnten.

Mein Puzzle von Sternbildern, bei dem ich alle Figuren des Reliefs auf Sternen verortete, ist in Stellarium seit ca. einem Jahr veröffentlicht. Ich habe in dieser Version die Figuren aufrechtstehend auf die Sterne gesetzt wie wir es von der Steinplatte her kennen und gewohnt sind. Ich glaube allerdings, dass manche der Figuren gedreht werden müssten, wenn man sie auf die Sterne setzt: insbesondere die unverstandene Gruppe von einem Mann, der ein Tier zähmt oder bändigt, die auf der Himmelsgegend von Andromeda-Cassiopeia liegen sollte. Wenn man sie aufrechtstehend auf die Sterne legt, findet sich kein sinnvolles Sternmuster, das irgendeinen Wiedererkennungswert hätte. Man kann sich allerdings gut denken, dass die angewinkelten Beine des Tieres durch die Zacken des Himmels-Ws in Cassiopeia imaginiert wurden, wodurch die menschliche Gestalt an der Stelle der Andromeda-Sternkette zu liegen käme. Solche Details werden wohl ewig im Bereich der Spekulation bleiben, solange man nicht weitere Quellen zur ägyptischen Uranographie findet. Es geht mir nicht darum, eine konkrete Anordnung von hellen Sternen mit einer Figur auf dem Dendera-Relief in Verbindung zu bringen – sondern, wie auch bei den Sternbildern der modernen Astronomie, die seit 1928 von der Internationalen Astronomischen Union kanonisiert wurden – wage ich den Figuren nur Flächen am Himmel zuzuordnen (allerdings viel gröber definierte Flächen als die exakten, orthogonalen Polygone der IAU).

Überraschend ist allerdings der Vergleich dieses Puzzles mit dem eckigen Zodiak und mit babylonischen Quellen. Auch hier erscheint der „runde Zodiak“ von Dendera wieder als Sonderling: Während die ägyptische Vorstellung der Himmelskuh sich stets auf Sirius bezieht und auch im „eckigen Zodiak“ von Dendera dementsprechend beschriftet ist, liegt die Himmelskuh im „runden Zodiak“ auf Prokyon, der den heliakischen Aufgang des Sternbildes Krebs (selbst nur mit schwachen, in der Dämmerung unbeobachtbaren Sternen ausgestattet) anzeigt. Auf dem Sirius hingegen liegt eine Gottheit, die Pfeil und Bogen in der Hand hält und die an die elamitische Ischtar erinnert – eine Göttin, die neubabylonisch auf diese Himmelsgegend projiziert wurde, um den Bogen und den Pfeil zu halten, die schon mittelbabylonisch dort gesehen wurden. Ägyptisch ist das Bild prima als Sathis verstehbar, die Göttin, die als Vorbotin der Nilflut gilt.

Südlich der Hydra finden wir einige weibliche Gottheiten: Hinter der Göttin mit Pfeil und Bogen (der Vorbotin der Nilflut) folgt die Nilflut (Anuket) und nach dieser folgen zwei weitere weibliche und eine männliche Gottheit. Die weibliche Gottheit ist eine Muttergottin, die zwar nicht ganz der typischen Darstellung der ägyptischen Muttergöttin Isis entspricht, aber sehr genau anderen Darstellungen von Muttergottheiten im Geburtshaus von Dendera – sie fügt sich also wunderbar in die Gesamtkomposition dieses Tempels. Die männliche Gottheit hält eine Hacke oder einen Pflug in der Hand, was auf einen Landwirtschaftsgott hindeutet – ebenfalls vom Zeichenstil her nicht typisch ägyptisch, aber typisch für den Isis-Tempel dieses Tempelkomplexes, auf dessen Außenwänden man derlei Gestalten oft abgebildet sieht. Die Ernte-Gottheit passt prima in diese Sternkarte, weil sich die Figur auf dem gleichen ekliptikalen Längengrad befindet wie Jungfrau und Waage, die typischen Erntezeit-Sternbilder.

Man könnte mit vielen anderen Beispielen weitermachen. Obwohl meine Identifizierung der Sternbilder also ein sehr wichtiges ägyptisches Gestirn, die Himmelskuh, „falsch“ (im Sinn von „unägyptisch“) deuten muss, bietet sie zahlreiche Vorteile zur Identifizierung von anderen Gestirnen: Der Stierschenkel (Großer Wagen) hat – unägyptischerweise – zwei weitere kleine Wesen bei sich: einen Schakal und ein nicht genau erkennbares liegendes felliges Tier. Es wird immer Löwe genannt, aber da sich der Schakal an der Stelle des babylonischen Sternbilds „Fuchs“ befindet und dieses kleine Fell-Tier an der Stelle des babylonischen Sternbilds „Mutterschaf“, wage ich die Hypothese, dass wir es hier mit einer babylonischen Sternkarte in ägyptisierter Darstellung zu tun haben. Vielleicht hat jemand einen babylonischen Himmelsglobus erstanden und dessen Sternbilder in ägyptischer Manier nebeneinander in ein flaches konzentrisches Raster gepresst. Dafür sprechen auch die Darstellungen mehrerer (definitiv im Original babylonischen) Sternbilder des Tierkreises. Das Mischwesen an der Stelle des Sagittarius ist beispielsweise ganz klar kein griechischer Zentaur, sondern der babylonische Gott mit Flügeln am Pferdeleib und einem Skorpionschwanz neben dem Pferdeschwanz. Im Unterschied zum babylonischen Gott hat er aber ein sehr ägyptisches Schiffchen unter dem Vorderhuf, das wir im 1. Jahrtausend auch babylonisch erwähnt finden.

The Dendera Zodiac

The zodiac is simply explained here: Aries, the ram, is shown as a little lamb. Taurus, the bull, as a (whole) bull, which is interesting because the Babylonian bull was probably always half (firstly, this is how it is seen in the sky, secondly, the celestial bull – as the constellation is literally called – is divided and sacrificed by the hero and his friend Enkidu in the Gilgamesh epic). Gemini, the twins, are the Egyptian sibling couple of the air god Shu and the humidity goddess Tefnut. Cancer, the crab, is often a scarab, Leo, the lion, is a lion. Virgo, which Babylonian originally did not exist as a constellation, but had been associated with the goddess Shala as the constellation Furrow and was only reinterpreted as this in the Uruk of the 1st millennium, is depicted as the goddess Shala in Dendera. Libra, the scales, and Scorpius, the scorpion, are depicted in the usual form. Sagittarius, although wearing an Egyptian double crown, is depicted like an (unusually Janus-faced) Babylonian god Pabilsang. Capricornus, the goatfish, is rendered unchanged as the benign Babylonian demon, Aquairus, the water sprite, is not rendered in the Babylonian form of the god of wisdom, magic power and the source of the Euphrates and Tigris, but as the Egyptian Nile god, which can be read as a direct translation of a foreign culture into one’s own. Remarkable is the image of the fish, which are depicted connected with a V-shaped band as described by Aratus, but which does not occur in Babylonian uranography. Significantly, these linked fishes line a rectangle of water that lies at the location of the Babylonian constellation “Iku” (an area measure). The zodiac figures thus all reveal at least Babylonian reminiscences, if not direct adoptions.

In addition to the twelve known figures, the zodiac also contains – then as now – the constellations Orion (Egyptian: Osiris), Ophiuchus (serpent bearer), Cetus (whale) and Sextant. What was historically in the place of Sextant, we do not know – perhaps it was simply empty. In place of the Greek Ophiuchus, there is a large deity on a throne in the image of Dendera, and in place of Cetus there are two female deities with wadjet sceptres. In both cases the meaning of these figures is unclear and certainly not Babylonian. Perhaps for Egyptologists smarter than I, they will someday provide a clue to older Egyptian constellations.

Apart from the “northern constellation”, whose central element is formed by the seven stars of the Big Dipper (Egyptian: bull’s leg), Orion-Osiris and the zodiac, which was after all originally (Babylonian, proven in MUL.APIN) the “path of the moon”, which (astronomically speaking) has not changed, there are only a few clues. The rest is filled in by interpolation. Based on these anchor constellations, we can therefore understand the representation of the “round zodiac” as a kind of planisphere, with the help of which other (older?) Egyptian constellations could possibly be opened up.

My puzzle of constellations, in which I located all the figures of the relief on stars, has been published in Stellarium for about a year. In this version I have placed the figures upright on the stars as we know and are used to from the stone slab. However, I believe that some of the figures would have to be rotated if they were placed on the stars: in particular the misunderstood group of a man taming or taming an animal, which should be on the celestial region of Andromeda-Cassiopeia. When placed upright on the stars, no meaningful star pattern can be found that would have any recognition value. However, it is easy to imagine that the bent legs of the animal were imagined by the prongs of the celestial W in Cassiopeia, which would make the human figure lie in the place of the Andromeda star chain. Such details will probably remain forever in the realm of speculation until one finds more sources on Egyptian uranography. My point is not to associate a specific arrangement of bright stars with a figure on the Dendera relief – but, as with the constellations of modern astronomy canonised by the International Astronomical Union since 1928 – I only dare to assign areas in the sky to the figures (though much more coarsely defined areas than the IAU’s exact, orthogonal polygons).

Surprising, however, is the comparison of this puzzle with the angular Zodiac and with Babylonian sources. Here again, the “round Zodiac” of Dendera appears as an oddity: while the Egyptian idea of the celestial cow always refers to Sirius and is also labelled accordingly in the “angular Zodiac” of Dendera, the celestial cow in the “round Zodiac” lies on Prokyon, which indicates the heliacal rising of the constellation Cancer (itself only equipped with faint stars unobservable in twilight). On Sirius, on the other hand, lies a deity holding a bow and arrow, reminiscent of the Elamite Ishtar – a goddess neo-Babylonian projected onto this celestial region to hold the bow and arrow already seen there in Middle Babylonian times. Egyptian the image is prima understandable as Sathis, the goddess who is considered the harbinger of the Nile flood.

South of the Hydra we find several female deities: Behind the goddess with bow and arrow (the harbinger of the Nile flood) follows the Nile flood (Anuket) and after her follow two more female and one male deity. The female deity is a mother goddess who, although not quite the typical representation of the Egyptian mother goddess Isis, corresponds very closely to other representations of mother deities in the birthplace of Dendera – so she fits beautifully into the overall composition of this temple. The male deity holds a hoe or plough in his hand, which suggests an agricultural god – also not typically Egyptian in terms of drawing style, but typical for the Isis temple of this temple complex, on whose outer walls one often sees such figures depicted. The harvest deity fits perfectly into this star map because the figure is on the same ecliptic longitude as Virgo and Libra, the typical harvest time constellations.

One could go on with many other examples. So although my identification of the constellations must “misinterpret” (in the sense of “un-Egyptian”) a very important Egyptian celestial body, the Celestial Cow, it offers numerous advantages for identifying other celestial bodies: the bull’s leg (Big Dipper) has – un-Egyptian – two other small creatures with it: a jackal and a not exactly recognisable lying furry animal. It is always called a lion, but since the jackal is in the place of the Babylonian constellation “Fox” and this small furry animal is in the place of the Babylonian constellation “Ewe”, I dare to hypothesise that we are dealing with a Babylonian star map in Egyptianised representation. Perhaps someone acquired a Babylonian celestial globe and pressed its constellations side by side in a flat concentric grid in the Egyptian manner. This is also suggested by the depictions of several (definitely Babylonian in the original) constellations of the zodiac. The mixed creature in the place of Sagittarius, for example, is clearly not a Greek centaur, but the Babylonian god with wings on the horse’s body and a scorpion’s tail next to it. Unlike the Babylonian god, however, he has a very Egyptian little ship under his front hoof, which we also find mentioned Babylonian in the 1st millennium.

Und die Moral von der Geschicht‘?

Ich denke, mit unserem Glauben, dass unsere Sternbilder „die griechischen“ sind, vergeben wir uns in der Forschung oft Chancen, weil wir alles – egal, ob griechisch, ägyptisch, babylonisch oder drittes – durch die Brille der modernen Interpretation von Almagest-Texten sehen. Der Almagest ist das letzte große Kompendium der Antike und wir wissen, dass die Sternbilder des islamischen und christlichen Mittelalters davon abstammen, dass diese in der Neuzeit weiterentwickelt wurden und glauben diese Transfer- und Transformationswege einigermaßen gut verstanden zu haben. Dass der Almagest aber nur früheres Wissen zusammenfasst und kanonisiert, scheint ein Trugschluss zu sein. Ja, er definiert einen neuen Standard – aber das heißt nicht, dass dies bereits vorher (unausgesprochen) ein Standard gewesen war. Besser wären wir dran, wenn wir die Sternkarten und -globen früherer Epochen für sich nehmen und nicht auf den Almagest „zurück“führen, der ja erst später geschrieben wurde. Nur so hat man die Chance einer wahren Geschichtsschreibung für die Entwicklung der Sternbilder – und die Geschichte, die sich dann ergibt, ist sicher weder ein Märchen noch überhaupt aus einem Guss: sie wird einen Haupterzählstrang mit mehreren Nebenhandlungen darbieten. Die Sternbilder in Ägypten dürfen also ruhig andere sein als in Uruk und dass die Sternbilder in Uruk im späten ersten Jahrtausend mitunter von den gleichzeitig in Babylon verwendeten abweichen, wurde bereits früher von anderen aufgezeigt (z.B. Steele 2018).

And the moral of the story?

I think with our belief that our constellations are “the Greek ones”, we often give ourselves opportunities in research because we see everything – whether Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian or third – through the lens of modern interpretation of Almagest texts. The Almagest is the last great compendium of antiquity, and we know that the constellations of the Islamic and Christian Middle Ages descended from it, that these were further developed in modern times, and we believe we understand these transfer and transformation paths reasonably well. But that the Almagest only summarises and canonises earlier knowledge seems to be a fallacy. Yes, it defines a new standard – but that does not mean that this had already been a standard (unspoken) before. We would be better off if we took the star maps and globes of earlier epochs on their own merits and did not “trace” them back to the Almagest, which was written later. Only in this way do we have the chance of a true historiography for the development of the constellations – and the story that then emerges is certainly neither a fairy tale nor from a single mould: it will present a main narrative thread with several subplots. So the constellations in Egypt may well be different from those in Uruk, and that the constellations in Uruk in the late first millennium sometimes differed from those in use at the same time in Babylon has been pointed out by others before (e.g. Steele 2018).