The Professor vs. the NSA

Today, Martin Hellman stands before a crowd of hundreds, narrating the history of his research in public key encryption. It’s foundational: internet security is built on mathematics, and Hellman (along with collaborator Whitfield Diffie) helped to fashion that math. Throughout the talk, you can see their adorable bromance: Diffie heckles from the front row, and Hellman banters right back.

Back in the 1970s, Hellman and Diffie couldn’t have known their work would lead to this stage. In fact, there was a likelier destination.

Federal prison.

“It’s July 1977,” Hellman tells the audience. “Whit and I are involved in a major fight with NSA over the data encryption standard.”

American law banned the unlicensed export of weapons. Makes sense: the government doesn’t want civilians wandering into Moscow with a trenchcoat full of fighter jet parts. The question is: Does this law apply to abstract mathematical ideas? By developing new approaches to cryptography, are Hellman, Diffie, and their collaborators de facto arms traffickers? If so, Hellman says, “then by publishing our papers in international journals, we are in some sense exporting plans for implements of war.”

“I think the penalty,” Hellman recalls, “was something like five years in jail.”

As a Stanford professor, Hellman sought the advice of the university’s general counsel, John Schwartz. Schwartz told him that, in his view, applying ITAR to cryptography research was unconstitutional—a violation of the first amendment. But he also warned that only a court of law could settle the matter.

His next words remain burned in Hellman’s memory.

“If you’re prosecuted,” Schwartz said, “we will defend you. If you’re convicted, we will appeal. But I have to warn you… if all appeals are exhausted, we can’t go to jail for you.”

It’s a line straight out of a Hollywood thriller, which cannot be said of most conversations in the faculty lounge.

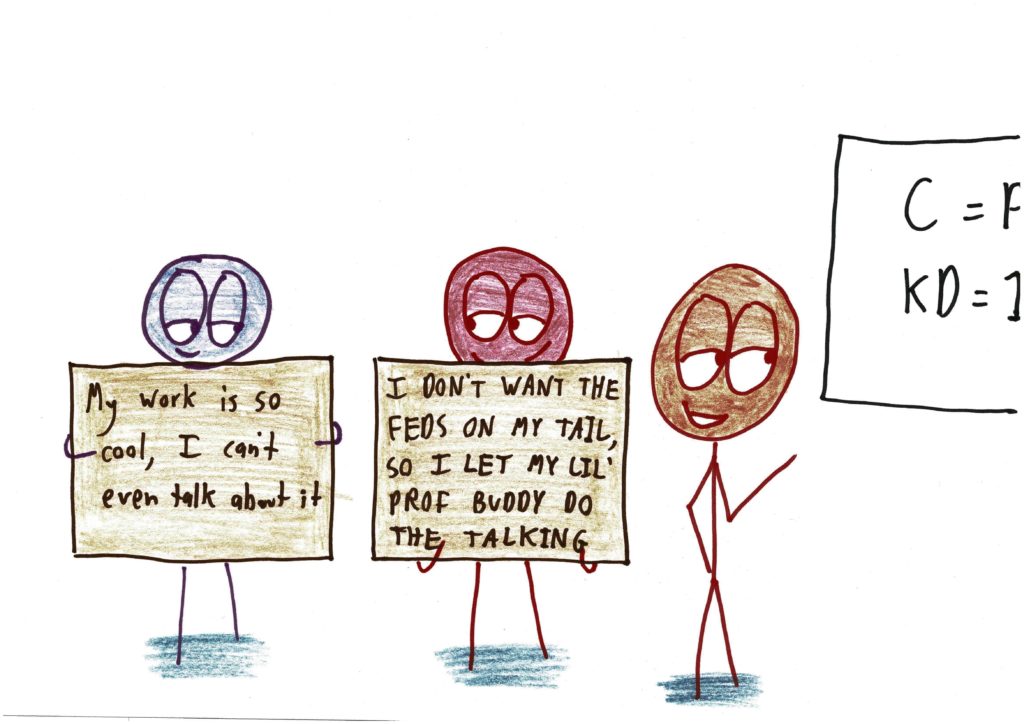

That October, Hellman planned to present two cryptography papers, co-written with students, at a conference. He intended to shine a spotlight on the students by having them give the talks.

Schwartz advised against it. “From a practical point of view,” Hellman says, “I was a tenured professor, and the students were just starting out.” That left them more vulnerable. “A multi-year court case could totally ruin a new PhD.”

The students courageously insisted on taking the risk—until their parents intervened. Hard to blame them: an academic career unfolds slowly enough, even without taking a five-year federal-prison hiatus.

“We came up with a very good system,” says Hellman. “When it was time for the papers, both of us went up… I explained to the audience, who already knew what was going on, that on the advice of Stanford’s general counsel, I would be giving the paper instead of the students. But from every perspective except legally, I wanted them to consider the words I was saying as if they were coming from the student.”

“And so,” Hellman explains, “the students stood there, not saying anything.” This bizarre visual amount to the best sales pitch a PhD could hope for: you as the ventriloquist, and a star professor as your cheerful dummy.

The conflict simmered until 1978. Then, out of the blue, Hellman received a call from the office of NSA director Admiral Bobby Inman to schedule a meeting.

“Whit and I had been fighting this out with the NSA in the press, and never actually talking to them,” remembers Hellman. “It’s a bad way to have a disagreement, and so I jumped at the opportunity.”

Weeks later, he found himself face to face with his adversary. Inman leaned over and said wryly, “Nice to see that you don’t have horns.”

Hellman looked back and said, “Same here.”

That broke the tension. Hellman soon learned that Inman had scheduled the meeting against the advice of all his senior colleagues at the NSA. But he, like Hellman, saw no harm in talking things out. “Out of that very cautious initial meeting grew, eventually, a friendship,” says Hellman. “That’s something we should keep in mind today, and not just in the cryptographic community.”

Hellman began his talk by joking that Diffie was his “partner in crime.” It was an offhand bit of humor; for the moment, he was not reflecting on how close they came to making that phrase literal.