Computer Pioneer Spirit: A lunch conversation with Fred Brooks

BLOG: Heidelberg Laureate Forum

We cannot ask Messieurs Daimler and Benz about their experiences with the first automobiles, but computers are just sufficiently recent for some of the pioneers to be still alive – and since those that were instrumental in the development of computers tend to be highly decorated by now, a number of them are around at the Heidelberg Laureate Forum.

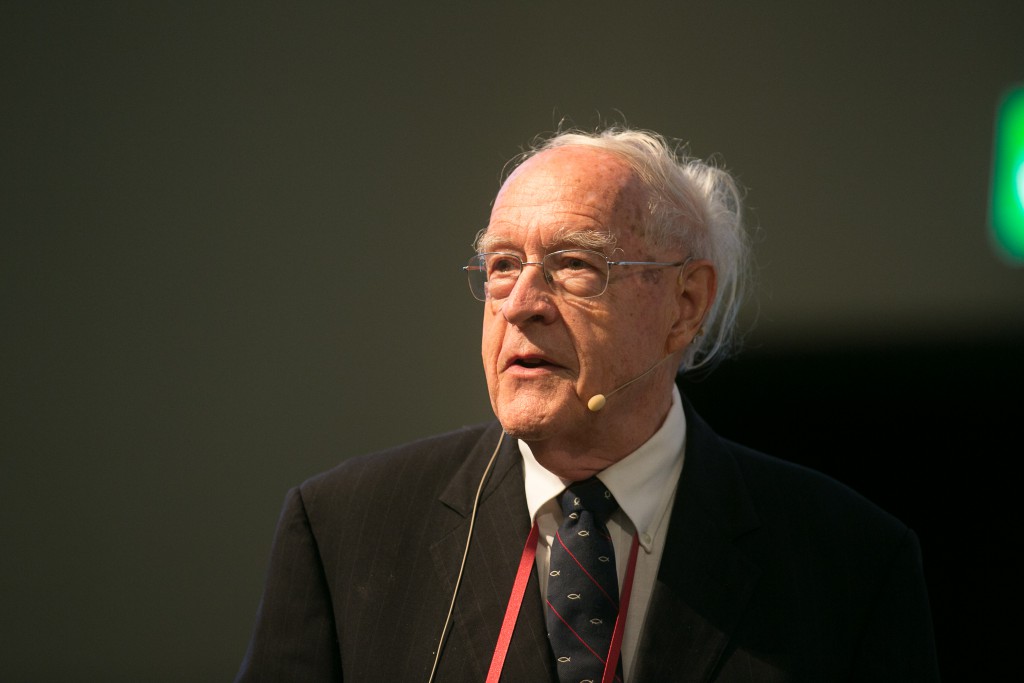

On Monday, I had a highly interesting lunch-queue conversation with Fred Brooks who, in the 1960s, was involved in the latest developments in (back then) mainframe computing first-hand, at IBM; today, Brooks gave a lecture on the same general topic, namely “A personal history of computers”. To me, the most poignant moments both of the conversation and of the lecture were those that made me realize how many things we take for granted today were up for discussion at one point or another – and that the decisions could have been different.

The fact that a byte has eight bits? Quite natural, I always thought; after all, eight is a power of two. Instead, this was the result of a business discussion of the 1960s, with good arguments on both sides: for keeping the old six-bit system, and for switching to eight bits. Some disadvantages of eight bits, economical: The switch would mean completely changing a considerable number of hardware devices, from tape storage (nine-track magnetic tapes – eight plus one parity bit – instead of seven-track) to printers, at a cost of millions of dollars. But there were good arguments from scientific computing, as well: four bits would mean too little numerical precision, eight bits too much precision for the calculations of the time, so six bits were a good compromise – with too much precision in thousands and thousands of little calculation, after all, your programs run for longer than they need to, and that was a big concern at the time. On the other hand, each chunk of 8 bits could represent more different characters than a 6-bit chunk. In particular, 8 bits could represent two digits from 0-10, an advantage where calculations involved a sizeable amount of digits, and did not need to represent much else.

Eight bits, in the end, were a business decision, made by Brooks. It led to heated discussions with Gene Amdahl, the architect of what was to be IBM’s first general purpose system, System/360. Amdahl had been the main proponent of staying in the six-bit world, and at the end of the day of decision, both Brooks and Amdahl independently handed in their resignations – only to be won back by one of their executive bosses the day after. Brooks regards the 8-bit decision as his greated impact on the world of computers.

Taking things for granted: Universal computers, not custom-made for a specific purpose but, lo and behold, usable for both scientific and commercial computing? A business decision in the 1960s. Mechanisms of technological breakthrough? More than one time, Brooks uses the phrase “and now the camel is in the tent” – discovering new uses for computers once they have been bought for rather different purposes, but are now present and usable: one model that spread as soon as it became cheaper than the four single-purpose accounting machines it could replace, another generation of computers as soon as they became small and cheap enough to be easily integrated with scientific instrumentation. (A computer on the department-level? No way, you’re creating competition for your university’s computing center! An instrument controller? That was OK.)

Text processing? The first example Brooks remembers is from a time when computer-based text processing would have been prohibitively expensive, except in very special circumstances – in this case the development of a new computer system; being able to print out the whole, updated documentation every day during the development process (from punchcards that made selective updates feasible) was a considerable business advantage in the development process.

Higher-level programming languages that needed to be compiled? Another struggle, and only won after the demonstration that the resulting programs could be as efficient as those assembled by a human programmer from scratch. (That, of course, at a time when computing time was at a premium – the opposite of today’s world with cheap computing power and in consequence, all too often sloppy and inefficient software.)

Other elements are more familiar: a six week orientation course for key IBM people at the National Security Agency, for example – to make sure IBM staff knew the specific demands of NSA work, and could keep those in mind when designing more machines.

Computer history is part of both our cultural and our technological heritage, and it is fascinating to hear the tales of computing machinery past, first-hand. And thanks to the HLF’s diligent video staff, anyone with access to a properly equipped (8-bits-to-the-byte and so on) computer can watch Brooks lecture online here.

Nice post. We really take many things for granted; I did not know about the 6bit vs 8bit debate. Nowadays 8bit makes perfect sense, but why not 6bit? Now I know.

I know Fred Brooks from his great book The Mythical Man Month and the article No Silver Bullet.

Great man.