From Synthetic Faces to Dogs in Berets: AI Can Now Create (and Edit) Hyper-Realistic Images

BLOG: Heidelberg Laureate Forum

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but if you’re an algorithm, it’s worth much more than that. The digital worth of 1000 words is just over 5,000 bytes, or 0.005 megabytes, whereas a photo, even a low-quality one, will be much larger.

For artificial intelligence, working with images has proven to be a greater challenge than working with text. But in the past few years, we’ve witnessed striking progress in this field as well. Now, AI seems to be on the cusp of finally being able to edit and create images – and that’s both thrilling and concerning.

This image was created by an AI from a text input of “Shiba Inu dog wearing a beret and black turtleneck.” Image courtesy of OpenAI DALL-E 2

Colorization and Minor Edits

A couple of decades ago, photographers using digital cameras had to be extremely careful with their setup. Lighting parameters could make or break a photo, and there was little room for error. Nowadays, deploying the right setup is still important for photographers, but you can get away with a bit more, as editing algorithms have become so much better and can compensate for some imperfections.

While selecting the right frame and capturing the image is still the photographer’s responsibility, a wide array of image editing options have become available, especially with the incorporation of AI into editing software. This works especially well if photos are saved as a “Raw” (minimally processed) file, which is more of a set of instructions rather than an actual image. This type of format enables smart algorithms to change contrast or brightness levels, correct colors, and even enhance images or add filters. When it comes to enhancing or deblurring, machine learning uses the color data of each pixel to estimate what the final photo should look like – it doesn’t always work yet (especially not like in the movies), but it has steadily progressed.

Another example of AI used for image enhancement is colorization: the process that adds realistic colors to black and white or sepia photos. This is especially useful for people looking to bring new life into old photos. It may not be accurate (AIs can only guess and produce realistic color patterns, not real color patterns), but it’s already surprisingly effective.

Colorizations, such as the one presented here, can colorize “by hand”, as is the case here, or with the aid of smart algorithms and AI, as is the case in the image below. Original black and white photo: Migrant Mother, showing Florence Owens Thompson, taken by Dorothea Lange in 1936. Image in Public Domain.

Same image, colorized with an AI released by the Singapore Government.

Another potential application of AI in image editing is the restoration of incomplete or damaged art, as was exemplified by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam when they used an algorithm to complete an iconic but cropped Rembrandt painting.

Creating Faces

But AI can do more than just edit images: it can create images. A particularly well-developed and important application is the creation of human faces.

We tend to trust our eyes when judging someone’s face, and most people would probably claim that they can distinguish a real human face from a synthetic one. As it turns out, we can’t. AI is already capable of creating indistinguishable human faces with a number of different traits and characteristics.

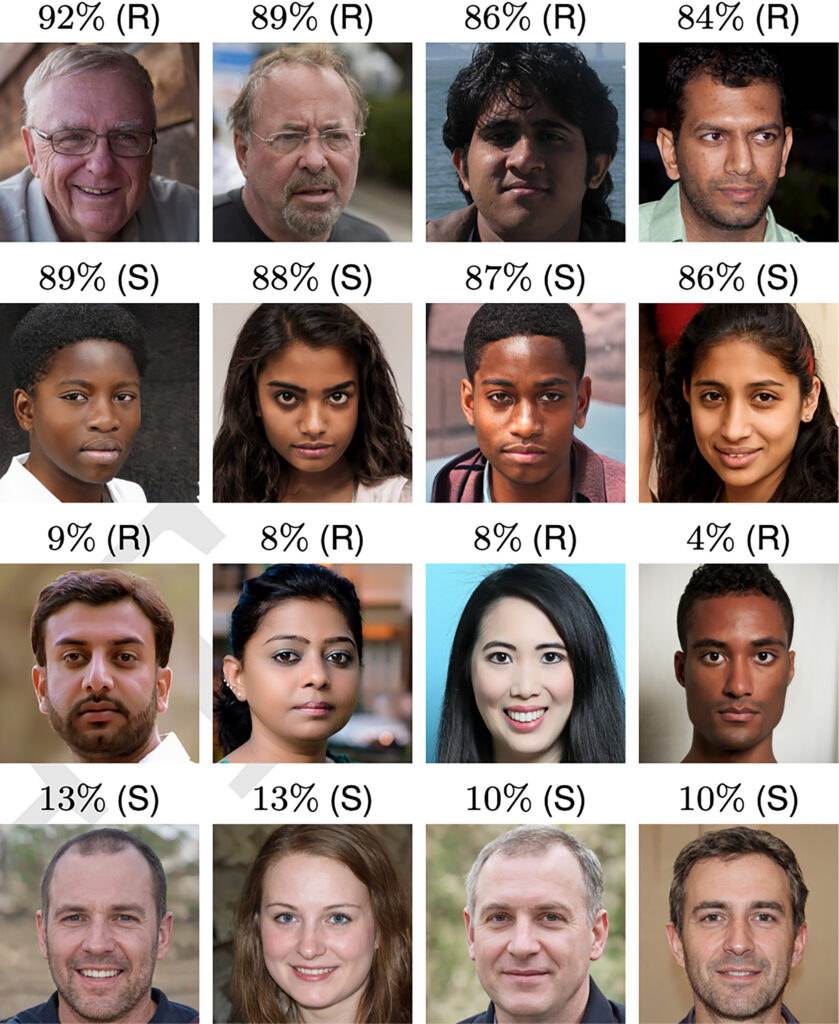

Try to guess which images are real and which are not. R=real; S=synthetic, the percentage indicates the success rate of a sample size of people identifying the nature of the faces. Image credits: Nightingale and Farid (2022), Open Access.

Not only are such faces indistinguishable from real faces, but they can be made to appear more trustworthy by changing parameters associated with face trustworthiness (for instance, faces with more feminine features were found to be more trustworthy). You can also customize these faces based on a number of parameters to tweak the end result (try your hand at it here).

Being able to create trustworthy faces can be important, for instance, for marketing. You can instantly attach faces to satisfied testimonials (which can also be AI-generated) to create the illusion of happy customers, or you can generate happy faces to associate with your product at no cost, instead of hiring actors and investing in image production.

You could also create fake profiles that can be nigh-indistinguishable from real profiles, and use them to promote products or services – or on the opposite, trigger bad reviews and cause problems for your competitors. Furthermore, you could create realistic bot profiles to fuel disinformation on Twitter or other social channels. With much of our activity slowly moving online, it even can be disconcerting to know that the “person” you’re interacting with online (and which has a human-looking profile image) may be nothing but an AI-generated figure.

Creating Everything in Every Style

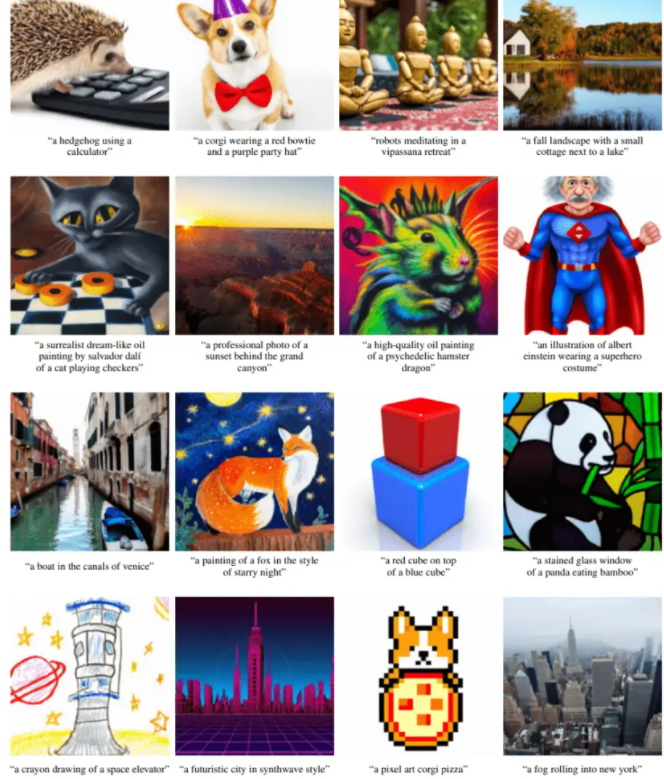

But faces are just the tip of the iceberg. We’re nearing a point where AI will be able to create any type of image from simple text input. Want to create an image of a boat in Venice? No problem. A psychedelic hamster dragon? Doable. An adorable Shiba wearing a beret and turtleneck? As you’ve seen already, it can be done.

Image credits: Nichol et al, Open Access.

Several promising algorithms can already produce striking results. Take, for instance, the work of Nichol et al, published in arXiv in late 2021, which uses diffusion models to produce imagery. Diffusion models start from existing images, which they corrupt progressively by adding Gaussian noise and wiping out details until only pure noise remains; then, a neural network is trained to reverse this corruption process, until the result resembles or is indistinguishable from the original. This type of approach can also be used for audio files as well. In their study, the researchers conclude:

“We observe that our model can produce photo-realistic images with shadows and reflections, can compose multiple concepts in the correct way, and can produce artistic renderings of novel concepts,” wrote the researchers in the pre-print server arXiv.

Perhaps even more striking is OpenAI’s new DALL-E AI. Based on the text-creating AI GPT-3 DALL-E (a portmanteau of artist Salvador Dali and the Disney robot WALL-E), it was meant to just be a proof of concept. Its creators wanted to see whether they could produce visual depictions from text input. The project received great interest, and recently, the second iteration of the AI (DALL-E 2) was released.

AI generated image from prompt: “Teddy bears working on new AI research underwater with 1990s technology.” Image credits: OpenAI.

OpenAI has been extremely careful to safeguard the algorithm, and it’s not hard to understand why. If you can create any image from any text input, you can create images of “politician-you-dislike slapping a baby” or add synthetic elements to real images to fuel misinformation – and as we’ve seen with the recent trend of misinformation, even imperfect fakes can be hard to spot for the untrained eye. Deepfakes, for instance, have been used to create false beliefs about Joe Biden’s health or to suggest a misleading link between deforestation and COVID-19 in Belgium.

As is often the case with technology (and AI in particular), it opens up a range of possibilities – but it also opens the way for biases and nefarious uses. For instance, when DALL-E is prompted to produce images of lawyers, it produces images of white men, but when it is prompted to produce images of flight attendants, the results are typically women. An AI used by major companies to aid employment was also found to favor men over women. Meanwhile, authoritarian governments are using AI to conduct state surveillance, and AI has even allegedly been used in assassinations.

Addressing these biases and the potential problems is a main challenge within the AI community, and OpenAI is not the only group looking to tackle these issues, but this could become a bit of an arms race, with algorithms becoming better at generating synthetic images, and opposing algorithms becoming better at detecting these images. However, when the human element comes into play, things are likely to get much more complex. We regularly see fake news being shared online, and the introduction of synthetic images can accentuate this problem. By the time a synthetic image is confirmed a fake, it may have already turned viral and swayed people’s opinions.

Ultimately, no matter how good or promising a technology is, it all comes down to how people choose to use it. AI can be used to foster equality or diversity or it can amplify biases already existing in society. Implementing it in a way that helps society may prove to be as big a challenge as developing the technology itself.

The Great Replacement

The basic idea behind the images and tools shown in this post is to create things and people that are indistinguishable from real things and real people, or indistinguishable from the productions of skilled craftsmen or artists.

However, this blurs the line between the human and the AI world and an AI program can now pass as a human. In fact, there has been a recent argument about how much Twitter traffic is generated by Twitter bots and how many Twitter accounts are bot accounts.

Thinking further, at some point there could be significantly more software bots than people and without the people who still exist even realizing it. So newscasters on TV or even TV presenters could be bots at some point and nobody would realize it. In such a world, perhaps even the complete disappearance of humans would not be noticed, at least not if bots could slip into bodies and populate the streets. Such human replacement bots would then perhaps use historical records from Google Maps about the frequency of visits to places in order to be in the right place at the right time. And if the very last real human being then consults the current visitor frequency of the Louvre, then he would only get numbers about the presence of bots and no longer about the presence of flesh-and-blood people.

Whereby: Visitor frequencies are already based on the (GPS) presence of mobile phones and not on the presence of people, and it is already a bold assumption to see a mobile phone as a proxy for a person.

Addendum: The Metaverse and Avatars can bring us into a world where the lines between real and virtual are blurred.

Abba Yoyage is currently presenting lifelike versions of the Swedish ABBA group members as they were 40 years ago.

The Guardian article

Abba Voyage Review: Stunning avatar act to copy reports on the shocking lifelikeness of this show.

Subtitled Any sense of not being in the presence of the band dissipates during a setlist of crowd hits, giving a glimpse of what to expect in the near future.

…Speaking of artificial intelligence

The human neural network functions fundamentally differently from a human algorithmically “fed” computer. Without going into detail here, the term “artificial intelligence” is misleading and, on closer examination, wrong. Since even more complex and nested algorithms – which are based on (information) mathematical connections – do not generate general-method solutions in particular. Even very complex interacting “algorithm clusters” do not simulate a biological thinking and decision making system.

All in all, it would first have to be clarified what intelligence means. A problem begins with standardisation. What is an intelligent decision? Already the independent, superordinate methodical finding of possible tasks is an (unsolvable) problem for a machine…

@Dirk Freyling(quote): „ Even very complex interacting “algorithm clusters” do not simulate a biological thinking and decision making system.“

Answer: 1) artificial neural networks are not well described by the term „algorithmic clusters“.

2) biological thinking and decision-making has not yet been researched so well that we could say exactly what the difference to artificial neural networks is.

Wenn man glaubt, ein Computerprogramm könne alles besser als ein Mensch, dann irrt man.

Beispiel Musik, mp3 bearbeitete Musik ist viel schlechter als analoge Musik.

Digital bearbeitete Fotos sehen beindruckend aus, sind aber nicht mehr real.

Wir haben uns zu sehr an die bunte Wunderwelt der Comics gewöhnt und schätzen nicht mehr die Realität.

@fauve:

Zitat: „ Digital bearbeitete Fotos sehen beindruckend aus, sind aber nicht mehr real.“

Jedes Foto ist bis zu einem gewissen Grade nicht real, weil (unter. anderem) die Aufnahmetechnik etwa die Empfindlichkeit für bestimmte Wellenlängen beeinflusst. Aber auch was wir selber sehen ist in ihrem Sinne nicht real. Unser Gehirn schafft zudem natürlicherweise das, was sie Comics nennen.